|

MAGISKA MOLEKYLERS WIKI |

Svensk förbudspolitik

InnehÄll

Underliggande artiklar

- Den svenska förbudspolitikens historia

- Förbudet mot kaffe, nykterhetsrörelsen och omröstningen om alkoholförbud

- Förbudet mot narkotika

- Försöken med en legal förskrivning av droger

- Bejerots ideologi blir rÄdande, ett narkotikafritt samhÀlle

- Lagen om att förstöra droger som inte Àr förbjudna

- Tidskurva alkohol/narkotikapolitik

- Granskning av partiernas narkotikapolitik

- Var stÄr partierna i narkotikafrÄgan?

- Vilka har anvÀnt narkotika?

- Antidrogorganisationer

- FMN, Hassela, RNS, CAN, Carnegieinstitutet, ENS 2000 / Stiftelsen Ett Narkotikafritt Sverige, Scientologerna, ECAD

- FaktakÀllor som anvÀnds av svenska förbudsföresprÄkare

- Skrifter frÄn Jan Ramström, Pelle Olsson, Thomas Lundqvist

- Haschboken

- Tongivande svenska förbudsföresprĂ„kareâ

- Granskning av argument frÄn bl.a Fred Nyberg och Kai Knudsen

Ăr den Svenska narkotikapolitiken framgĂ„ngsrik?

För oss Svenskar beskrivs oftast den förda politiken som nÄgonting vi ska vara stolta över. Det Àr en framgÄngssaga, vi har lyckats bÀttre Àn övriga Europa, kanske Àr vi rent av vÀrldsmÀstare i grenen "Narkotikafritt samhÀlle". Denna synen förmedlas till oss frÄn bÄde antidrogorganisationer och politiker:

| â | "Vi Ă€r bĂ€st i Europa, jag skulle nĂ€stan sĂ€ga att vi Ă€r bĂ€st i vĂ€rlden" â Maria Larsson (kd) enligt kolumnist i Metro 2012-03-21[1] |

â |

I Europa har man en annan syn pÄ den svenska drogpolitiken, den Àr inte lika munter.

Tim Boekhout van Solinge frÄn "The Centre for Drug Research" (CEDRO) i Amsterdam sammanfattade i en artikel frÄn 1997 synen pÄ Sveriges narkotikapolitik. Det Àr klarsynta betraktelser som nÀstan 20 Är senare fortfarande Àr lika aktuella och delas av forskare och politiker i andra EU-lÀnder. Sverige Àr landet med extremisterna som i debatterna om narkotika ger ett mycket underligt intryck:

| â | Since Sweden has become member of the EU, it has quickly gained a reputation being one of the leading countries opposed to any drug liberalisation initiatives. The way this is done by Swedes, for example in EU meetings in Brussels and the European Parliament, sometimes leaves a strange impression on other nationals. This holds true not only for government officials and politicians, but even more for militants like Torgny Pettersson who is working both for European Cities against Drugs (ECAD) and the Hassela Nordic Network (HNN).

When the Swedish drug policy is criticised by foreigners, something very deep and fundamental seems to be being touched. Whereas Swedes are usually rational and calm, when drugs are discussed, rationality seems very distant and emotions get the upper hand, which in the Swedish context and in the light of their debating culture is very unusual. A foreigner criticising Swedish drug policy can trigger violent reactions. One gets the impression this criticism is interpreted as an attack on something profund and very Swedish, which almost automatically leads to a nationalistic sense of oneness. Possible explanations for these kind of reactions can be found in what was mentioned previously, namely the broader, symbolic function the drug policy has within Swedish society, as shown by Tham, and before him by Christie & Bruun. In this respect one should also take into consideration the magnitude of the Swedish drug education programmes and their impact. The massive drug education programmes start in the primary schools and regularly recur throughout the school curriculum. Without exaggeration, this opinion forming could be described as a process of indoctrination. Considering the magnitude of these programmes, the contents of them have gradually become something so indisputable and conclusive that one incorporates them into ones own value system. Because the ideas have become part of ones inner life, there is hardly any possibility of putting things into perspective or looking upon them in a rational fashion. Attacking or questioning these basic tenets, can then trigger violent reactions. In this perspective, a comparison can be made with democracy. Most people in Western societies do not question the concept of democracy since the virtues of the political model have been so internalised one no longer questions its principles; it is something one simply takes for granted. Questioning the concept of democracy, can lead to reactions that are similar to criticism of Swedish drug policy. |

â |

Man kan Àven notera att Sverige sedan intrÀdet i EU Àven satt kÀppar i hjulen för den europeiska liberaliseringsvÄgen:

| â | The debate about the Swedish drug policy intensified after Sweden (as well as Austria and Finland) joined the European Union in 1995. Of all three new European Union members, Sweden was arguably pursing the most restrictive drug policy. Given its low rate of drug abuse compared to other European Union Member States, the policy of Sweden was seen as successful and there were repeated references to the Swedish model in drug policy discussions. However, this development was not welcomed by all. While the statement of one researcher that Swedenâs entry into the European Union âparalyzed the general trend towards liberalism that had been developing,â is probably an overstatement, it is true that a harmonized European Union drug policy remains an elusive goal. Nonetheless, States members of the European Union are parties to the United Nations treaties and thus bound by their provisions. â Antonio Maria Costa, UNODC (2007)[3] |

â |

Man har Àven samma instÀllning mot andra lÀnder i vÀrlden. Exempelvis 2011 i FN dÄ man röstade mot Bolivia, vars enda önskan var att tillÄta kokablad för den inhemska befolkningen som tuggat den i tusentals Är. Det sÄgs av Sverige som ett svek mot alla andra lÀnder kÀmpar mot narkotika (LÀs mera i kapitlet GenomgÄng av lÀnder med en tillÄtande narkotikapolitik).

Förutom att ha den sjÀlvuppfattade rollen som "bÀst i klassen" sÄ försöker alltsÄ skoleleven Sverige pÄtvinga sin repressionistiska och "framgÄngsrika" modell pÄ hela klassen och nedvÀrderar alla andra modeller. Men Àr den egna modellen verkligen sÄ framgÄngsrik? Och Àr den effektivast pÄ att frambringa den mest optimala folkhÀlsan för pengarna?

Henrik Tham, professor i kriminologi vid Stockholms Universitet skriver i en artikel frÄn 1998 att det Àr mycket svÄrt att se att sjÀlva politiken ledde fram till nedgÄngen i narkotikabruket under 1980-talet, samt att man inte kan se att ökad repression ger önskad effekt:

| â | Swedish drug policy is partly based on the assumption that serious (primarily intravenous) drug abuse can he prevented by inhibiting cannabis use. It is disputable. however, that the 'total consumption model' that is applied to legal alcohol use can be translated without modification to the field of illegal drug use. And this dispute can only be settled empirically.

... A change in the Drug Offences Act in 1993 gave the police the power to use blood and urine samples to establish drug consumption. Among the aims of the change in the law was that of âproviding possibilities to intervene early, and to coercively prevent young people getting entangled in drug abuse" (Proposition 1992/93, p. 142, 1). A collation of the convictions for âown useâ of drugs in 1994 shows that young people with no previous convictions have in fact been targeted to a very limited estent. Obviously a few âFirst time usersâ are arrested and convicted. But 80% of those convicted of the consumption of illegal substances are individuals with at least one prior contact with the criminal justice system (and 62% have a prior record of drug offences). A bare 6% of those convicted are both young (15 to 20 years old) and previously unknown to the police. The police use of the law and of blood and urine tests seems primarily to be aimed at older and well-known criminal drug users slightly more often than usual (source: Statistics Sweden, computer print out: see also Von Hofer 1935, Table IV:3; du RĂ©es Nordenstad 1996; Anderson 1997). It is of course possible that this use of police resources has a good deterrent effect so that fewer individuals start using drugs, however, the school and military conscript studies suggest no such effect - both show clear upward trends since 1993 (see Figure 1). CONCLUSIONS From the official point of view, the shift in Swedish drug control since 1980 towards a stricter model, has been successful when compared with the earlier, more lenient drug policy. As far as estimating the success of the 'restrictive' Swedish model is concerned, no serious attempt has been made at an authoritative evaluation. Available data do not verify the official picture. The decrease in new drug users was particularly marked during the more lenient period in the 1970s. The extent to which this reduction has continued during the 1980s is primarily a question of interpretation since different measures produce somewhat different answers. And in the 1990s some indicators point upwards - in spite of the increasing severity of the policy. The Swedish policy is also marked by a clearly normative approach. The use of drugs is regarded as a problem per se. As a consequence, much stress is being put on attempts to reduce the experimental use of drugs. The importance of using legislation to make a moral stand against drugs, of showing the societal rejection of drugs, is stressed over and over again. Health arguments are seldom allowed to enter the debate and the pattern of drug-related mortality has rarely been broadcast by those with an interest in the drug problem. ... Finally, the uncertain and limited reduction in drug use and abuse since the beginning of the 1980s has to be seen in relation to the clear increases in the costs of drug control. These control costs include a disregard for legal principles, increased exploitation of limited law enforcement resources, compulsory treatment programmes, more and longer prison sentences and possibly increased mortality. The focus on repression has become increasingly obvious in Swedish drug policy. |

â |

En rapport frÄn FN:s organ mot brott och narkotika (UNODC) som publicerades 2007 hyllar den svenska modellen och framstÀller den som framgÄngsrik. Detta lyfts givetvis fram i svensk media och av förbudsföresprÄkare[5] som ett bevis pÄ att vi Àr bÀst. Bland dom fÄ kritiskt granskande styckena som förekommer i rapporten gÄr man in pÄ att man inte kan se nÄgra effekter frÄn de senaste större lagskÀrpningarna:

| â | Drug abuse became a punishable offence in 1988. At the time, it was argued that this was necessary âin order to signal a powerful repudiation by the community of all dealings with drugs.â In addition, it was felt that criminalizing personal consumption would have a preventive effect, particularly among youths. Further emphasis was placed on the importance of adopting a uniform approach within the Nordic countries- drug use was already an offence in Norwegian and Finnish legislation. The most severe punishment was a fine.

In 1993, the law was further tightened by introducing imprisonment into the scale of punishments (1992/93:142). Police were now empowered to undertake a bodily examination in the form of urine or blood specimen test where there are reasonable grounds to suspect drug use. The purpose of the more severe provision was to âprovide opportunities to intervene at an early stage so as to vigorously prevent young persons from becoming fixed in drug misuse and improve the treatment of those misusers who were serving a sentence.â However, in an evaluation of the criminal justice system measures, the National Council for Crime Prevention of Sweden concluded that âbased on available information on trends in drug misuse there are no clear indications that criminalization and an increased severity of punishment has had a deterrent effect on the drug habits of young people or that new recruitment to drug misuse has been halted.â On the contrary, the Council found that drug experimentation among young people, increased throughout the 1990s, a trend, which was similar in Sweden to that in other countries. |

â |

En intressant notering Àr att Sverige Àr en av UNODC:s största bidragsgivare. Rapporten kanske var ett tack till Sveriges regering? 2007 uppgick bidraget till 105MSEK[6], pÄ senare Är har dock summan sÀnkts[7].

Rapporten vÀckte Àven en del kritik. MÄnga har uppfattningen att det finns andra förklaringar Àn att narkotikapolitiken orsakat Sveriges lÄga prevalens:

| â | Costa's suggestion that there is a obvious causal relationship between prevalence and UNODC-style drug control policy appears unsustainable. Various countries have comparable or lower levels of drug use than Sweden but have very different drug policies. Greece, for example, (according to the EMCDDA), has the lowest level of drug use in Europe but spends approximately one-fiftieth on per capita drug-related expenditure that Sweden does. Holland, also has well below the European average drug use, spends more than Sweden per capita, but has a tolerant / harm reduction-led policy that is the polar opposite of the Sweden UNODC model. Conversely, another repressively oriented country - third in the Euro drug-related expenditure tables - is the UK, which sits at the top of most European drug use prevalence tables. We have yet to see a UN report titled 'The UKâs unsuccessful drug policy: a review of the evidence', indeed if the UK Government buys into Costa's analysis they must be wondering what they have done to 'deserve' our high prevalence rates.

The alternative theory, one not based on the UNODC's public relations crisis and overtly political prerogatives, would be that levels of drug use are determined by a complex and highly localised interplay of multiple social, cultural, economic and demographic variables, and that government drug policies, specifically enforcement and prevention efforts, have, at best, only marginal impacts. Dr Peter Cohen, Director of the Centre for Drugs Research at the University of Amsterdam, has argued that Sweden's low level of drug use and repressive drug policy, rather than being causally linked, are in fact both merely expressions of its historically temperance oriented culture, noting that Sweden also has historically low levels of alcohol, tobacco and prescription drug use. It is also worth pointing out that Sweden has low levels of social inequality, social deprivation, and unemployment, combined with a very high level of health and social welfare spending. |

â |

| â | Maybe Sweden's drug policy is just another phenomenon on its own, next to low levels of alcohol and drug use, that EXPRESSES a temperance culture, but does not cause it. In other words, even if Swedes were to choose a less extreme policy, their temperance culture would still produce low levels of intoxicant use, lower than some but not all countries.

The Greeks, using little alcohol and drugs as well, will produce their own low figures from a series of completely different cultural or demographic characteristics and determinants, as do the Dutch. Nothing contradicts the thesis that drug policies, whatever they may be, have little to do with the production of the drug and alcohol situation that is found. For UNODC to even contemplate this 'cultural construction' notion would be disaster, because it opens the road to a scientific analysis of drug situations, separating it from the ideological analysis that suits UNODC. And this notion would completely invalidate Mr. Costa's conviction that countries have the drug problem they 'deserve' if they fail in drug control orthodoxy. |

â |

I en artikel frÄn 2009 sÄgar Börje Olsson, professor i samhÀllsvetenskaplig alkohol- och drogforskning vid Stockholms Universitet, i princip hela rapporten samt belyser Äter igen faktumet att det inte finns nÄgon forskning som talar för att Sveriges narkotikapolitik Àr speciellt framgÄngsrik:

| â | The concluding description of the Swedish drug policy development covering the last 15 years is quite superficial, idyllic, without analysis or critical approach, and the wording not only reminds the reader of the formal and empty style of an overriding committee report, is basically a summary and translation of the national action plan on drugs. What is basically said is that the policy model that was built up has proven to be efficient even if the economic recession during the 1990s led to some imbalances which were restored as times got better. As a kind of general conclusion, it is said: âThe current policy model was successful and has therefore been maintainedâ (p. 19). This conclusion is drawn already before the report has presented the drug situation in Sweden and analysed it in relation to the drug policy.

... The report states that the investments in drug policy in Sweden have paid off. âAs has been shown in this report, the prevalence and incidence rates of drug abuse have fallen in Sweden...â (p. 52). This conclusion can, as has been discussed in this paper, quite easily be questioned and probably also repudiated all together, and any claims that it has been shown that different drug policies have caused use and problem use to go up or down is simply false. No serious scientific attempts to analyse such relations exist in Sweden, and the few that might be used to discuss these matters show, on the contrary, that there are no significant effects on the drug use levels. Recently, this lack of knowledge has in fact been acknowledged by representatives of Swedish authorities. In a publication from the National Public Health Institute, âthe state of artâ of Swedish drug policy is reviewed and in the introduction the authors clearly admit that ââŠthere is no scientific basis to state that the restrictive Swedish drug policy is superior to other policiesâ (AndrĂ©asson, 2008, p. 9). This message was stated even more clearly through media when the report was published. Despite this awareness the Institute continues to tread in the old footsteps and has succeeded to produce a book with idealized and highly coloured descriptions of drug policy and drug use developments which in large resemble those of the UNODC report. An alternative description of the drug situation in Sweden over the last years gives a different flavour to what problems the society presently has to challenge. Sweden has never before had as many problem drug users as during recent years, a growing proportion of this population belong to the younger age cohorts, heroin is increasing its share and has by now probably overtaken the position as the dominant drug on behalf of amphetamines, treatment demand is on the rise and drug-related deaths remain on a high level with a possible increase during the very last years, the number of intravenously contaminated drug users with HIV is increasing and the proportion of addicts with various forms of hepatitis is very high, drug crimes are going up, the number and proportion of drug addicts in prison has risen to levels of about 60 %, and the availability of drugs is higher than ever indicated by increased numbers and amounts of drugs seized and falling drug prices. Life-time prevalence among the general population and certain younger age groups have varied over the last 40 years, but it is not possible to link such variations to the development of problem drug use or different harms linked to drug use. ... The report is generally tendentious with a clear ambition to picture the Swedish drug policy model as successful. In fact, this ambition leads to a report with so many big errors and unsupported conclusions that it does not meet any scientific criteria. This is serious, since it makes it more or less impossible to get sight of what in the Swedish society that can have had positive effects on drug problems. |

â |

Forskaren Christopher Hallam gör nÄgra noteringar om baksidorna med Sveriges narkotikapolitik:

| â | ...in its treatment interventions, Sweden is untypical in its determination to enforce abstinence upon the recalcitrant drug user, rather than manage the consequences of use and ameliorate their severity. This emphasis, it should be noted, is not viewed in punitive terms by its advocates, but rather as providing protection, assistance and support; it bears a strong resemblance to the American discourse of âtough loveâ. As Goldberg has observed, a key assumption underlying the Swedish conception of drugs is that the user is âout of controlâ, with individual self-will having been replaced by the drugâs own âchemical controlâ, or, in a version theoretically elaborated by the psychiatrist Nils Bejerot (discussed below), controlled by instinctive drives that subvert rationality. Thus, the dependent user needs the society to take control back from the drug, by coercive means if necessary.

... ...the Swedish approach is characterised by the continuous application of a generalized repression. As stated by the Police representative to a government task force in 1990: âWe disturb them (the drug users) in their activities, and threaten them with compulsory treatment and make their life difficult. It shall be difficult to be a drug misuser. The more difficult we make their living, the more clear the other alternative, i.e. a drug-free life, will appear.â ... As noted previously, official figures estimate there to be approximately 26,000 problem drug users in Sweden, though again the actual numbers may be higher. The problem drug use prevalence rate is put at 0.45% by UNODC, slightly below the EU average of 0.51%. Nonetheless, UNODC acknowledges that problematic drug use as a proportion of overall drug use is very high in Sweden. 1 in every 5 to 6 Swedish users is included in this category, compared with 1 in every 12 or 13 in the UK ... Whether or not Swedenâs policies are âsuccessfulâ depends on the definition of success and the strategic measures in which that definition is embedded. In its own terms, the Swedish government can claim success as a result of the countryâs relatively low prevalence of recreational drug use. This claim is endorsed by the Executive Director of UNODC, on the basis that low prevalence constitutes the most important policy objective. In terms of the management of harms associated with drug use, however, particularly as these are linked to dependent patterns of drug consumption, it is much more difficult to consider the strategy as successful. Harm reduction and other public health measures seem inadequate to meet the realities on the ground, and the restrictive model may in fact exacerbate this situation. The failure of Sweden to address these associated harms is undoubtedly linked to the âvisionâ of a drug free society, which militates against a pragmatic response to these health challenges. As with most utopias, the Swedish system does not deal well with those obdurate realities (such as the continued use of drugs in sometimes risky ways) that fail to fit into its design for perfection. |

â |

Professor Ted Goldberg om den svenska synen pÄ missbruket och metoderna man anvÀnder för att stÀvja det:

| â | It is important to note that school surveys measure recreational rather than problematic consumption, and more than 90% of those who have tried drugs in Sweden never go beyond the former stage (Goldberg, 1999b, p. A4). By calling everyone who uses any drug a misuser the rates for problematic consumption tend to disappear. But it is problematic consumers not recreational consumers who bear the problems usually associated with illicit drugs, i.e. unemployment, criminality, prostitution, premature death, HIV, hepatitis, etc. So it is important to note that while Sweden has comparatively few recreational consumers â about half the rate of the Netherlands where 17% had tried cannabis according to the 2001 survey (Abraham, Kaal & Cohen, 2002, p. 121) â our best guess based on available studies is that both countries have approximately the same number of problematic consumers. (See Olsson et al., 2001, p. 36; Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport [VWS], 2001, p. 9) If the dominant theory in Sweden was accurate then the much higher incidence of recreational consumption in the Netherlands should have produced an equivalently higher rate of problematic consumption as well.

Since this is not the case, the theory must be questioned as other mechanisms reasonably should be of primary importance in explaining the development of problematic consumption. This serves as another example of how Swedish drug policy has prevailed despite the existence of contradictory evidence. The biochemical dependency theory implies that it is not necessary to maintain clear distinctions between different kinds of consumption or use patterns. Rather, the reduction of all forms of consumption are treated as equally important, as sooner or later physiological changes will transform recreational consumers into problematic users." "Based on Bejerotâs theory, it has become almost axiomatic in Swedish thinking that euphoria underlies all drug consumption. This theoretical blind spot is another reason why Sweden has failed to distinguish between different kinds of consumption. While many recreational consumers use illicit drugs to achieve positive states (some of which might be called euphoria), it is assumed that all consumers must share this goal. This misconception may be exacerbated by responses problematic consumers commonly give in interviews. When asked, they most often report that they take drugs to achieve some positive state. One reason for this response is that problematic consumers most often think and act in relation to short-term goals, and, in the short term, drugs may appear to help them deal with their current problems. For instance if they are frightened, drugs may eradicate the feeling for a few hours. In sharp contrast, the author has spent years conducting participant observation research on the drug scene in Stockholm, holding many intimate conversations with problematic consumers, and these accounts paint a very different picture. Many problematic consumers speak about how their lives are deteriorating and believe that in the long run they will destroy themselves if they do not quit using drugs. In other words, they are aware that the life they are leading is self-destructive. Yet, in spite of the harm, they continue consumption (see Goldberg, 1999a). So when speaking of aims behind drug consumption, it is important to distinguish between problematic and recreational consumers. While both may use drugs for short-term gains, recreational consumers will reduce or even terminate consumption when and if the long-term effects become self-destructive, as this is incongruous with their life goals. On the other hand, problematic consumers, have extremely negative self-images, making them feel they deserve to be destroyed (Goldberg, 1999a). Their drug consumption is an important means towards this end. Swedish drug policy does not even consider the self-destructiveness of problematic consumers. On the contrary, based on the idea that euphoria lies behind consumption, it is believed that if we can make life on the drug scene as difficult as possible, living in the straight world will seem a better alternative. Logically this should encourage problematic consumers to abstain from drugs, and so the police use their limited resources to intervene at the street level (Socialdepartementet, 1991, p. 11). It also explains why some social workers spend their time making life difficult for drug consumers rather than trying to alleviate their misery. These persons refuse to talk to clients while they are under the influence, feed information to the police, threaten to take custody of the children of clients who do not âvoluntarilyâ accept treatment, etc. There have also been some extreme cases reported. For instance, social workers in a Stockholm suburb who had a project for youths who had taken drugs were censured by the National Board of Health and Welfare for: (1) not informing the adolescents and their parents of their rights; (2) forcing even those who did not have alcohol problems to take Antabuse; (3) being manipulative; (4) using illegal coercion; (5) concentrating on mechanical control instead of building up a mutual relationship; and (6) not having a documented treatment plan based on an individual evaluation of each client (Socialstyrelsen, 1990, pp. 3-8). The social worker responsible for this censured program was also vice chairman of the National Association for a Drug-free Society (RNS), a nationwide organization founded by Nils Bejerot, and one of the principal lobby groups behind current Swedish drug policy. |

â |

2015 fÄr Sverige kritik av FN-kontoret för mÀnskliga rÀttigheter:

| â | Sveriges narkotikapolitik fĂ„r tung kritik av FN-kontoret för mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter. Flera vĂ„rdinsatser för droganvĂ€ndare, som sprututbyte, Ă€r bara delvis eller inte alls införda hĂ€r. Detta Ă€r inte förenligt med mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter, menar FN.

â Vi brukar betrakta Sverige som ett föregĂ„ngsland med vĂ€ldigt progressiv politik. DĂ€rför blev jag förvĂ„nad över att se hur landet ligger efter i narkotikafrĂ„gan, sĂ€ger den bitrĂ€dande högkommissionĂ€ren för mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter, Flavia Pansieri, nĂ€r SVT trĂ€ffar henne i GenĂšve. ... Lever svensk narkotikapolitik i det hĂ€r avseendet upp till kraven pĂ„ mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter? â Nej. Sverige behöver se över behovet av att garantera vad som Ă€r ett grundlĂ€ggande ansvar för alla stater vad gĂ€ller mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter, nĂ€mligen att garantera alla individer bĂ€sta möjliga hĂ€lsa och skydda dem frĂ„n diskriminering, sĂ€ger hon. â Sverige brukar vara ett föregĂ„ngsland pĂ„ mĂ„nga omrĂ„den vad gĂ€ller statens ansvar för sina medborgare. Jag Ă€r förvĂ„nad att det hĂ€r omrĂ„det inte Ă€r sĂ„ utvecklat. |

â |

Drogpreventionen i skolorna Àr verkningslös

Politiker och förbudsföresprÄkare brukar ange drogpreventionen i skolorna som en förklaring till att fÄ har anvÀnt droger i Högstadie/gymnasieÄldern. Men det mesta tyder pÄ att den förklaringsmodellen Àr felaktig, vilket betyder att en kvarts miljard kronor som kunde satsats pÄ reformer med vetenskapligt stöd, exempelvis skademinimerande ÄtgÀrder, istÀllet gÄr till spillo varje Är. NÀr det gÀller drogpreventionen Àr det svÄrt att se nÄgra alternativ som tydliga effekter[14].

Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvÀrdering slÀppte 2015 en systematisk litteraturgenomgÄng av studier och annan forskning som finns pÄ omrÄdet. Man kommer fram till att de existerande drogpreventionsprogrammen har liten eller ingen effekt pÄ att förebygga exempelvis cannabis:

| â | Inget av de manualbaserade programmen för skolan har visats fungera allmĂ€nt drogförebyggande. Enstaka program har visats kunna minska konsumtion av tobak eller cannabis eller tungt episodiskt drickande. Effekterna Ă€r vanligen i storleksordningen 1â5 procent. Det vetenskapliga stödet rĂ€cker inte för att dra nĂ„gra slutsatser om effekten av manualÂbaserade förĂ€ldrastödsprogram i grupp. Skol- och förĂ€ldraÂstödsprogram har i nĂ„gra studier lett till ökad konsumtion. â Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvĂ€rdering (2015)[15] |

â |

| â | I den senaste budgeten satsade staten 259 miljoner kronor pĂ„ förebyggande Ă„tgĂ€rder mot alkohol, narkotika och tobak, varav det mesta lĂ€ggs pĂ„ barn och ungdomar i skolan. Till det kommer de miljoner som landstingen och kommunerna satsar.

...av 100 personer sĂ„ pĂ„verkar du mellan en och fem personer, sĂ€ger Kent Nilsson. TT: Men Ă€r 1-5 procent tillrĂ€ckligt? â Jag Ă€r tveksam. Man bör i stĂ€llet satsa pĂ„ att utveckla metoder och göra dem bĂ€ttre. Vi ska ocksĂ„ vara medvetna om att det hĂ€r Ă€r en industri, att det finns företag som tjĂ€nar vĂ€ldigt mycket pengar pĂ„ det hĂ€r. Men man mĂ„ste vĂ„ga fasa ut ineffektiva metoder, Ă€ven om det finns ett motstĂ„nd, sĂ€ger Kent Nilsson. |

â |

Till "Industrin" tillhör naturligtvis alla antidrogorganisationer som verkar i Sverige. De fÄr stora delar av sin inkomst frÄn skattefinansierade medel i form av bidrag och betalning för att de hÄller föredrag i kommunerna, dÀribland pÄ skolorna dÀr barn och ungdomar matas skrÀckpropaganda och fÄr lyssna till gamla missbrukare som berÀttar om sina miserabla upplevelser i knarktrÀsket. Dessa organisationerna föresprÄkar naturligtvis mer av samma vara för att minska narkotikakonsumtionen och Àr motstÄndare till Kent Nilsson och andra forskare som utvÀrderar resultatet av deras jobb.

Polisens resurser riktas Ät fel hÄll

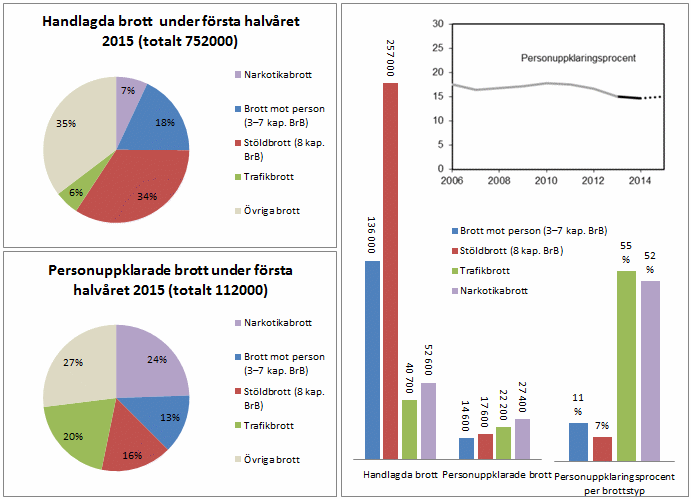

Legaliseringsguiden har sammanstÀllt ett diagram som bygger pÄ statistik frÄn Brottsförebyggande rÄdet 2015[17]. Statistiken visar att narkotikabrott stÄr för en liten andel av anmÀlningarna, men en stor andel av de uppklarade brotten.

Av alla handlagda (Àrenden som hamnar hos polisen) sÄ Àr det bara 51% som utreds, resterande anmÀlningar lÀggs ner omedelbart dÄ man anser sig sakna spaningsuppslag. Endast omkring 15 procent av de handlagda brotten personuppklarades (genom ett lagföringsbeslut). Det Àr en siffra som legat stabilt över lÄng tid.

Stölder och brott mot person (misshandel, rÄn, vÄldtÀkter, etc.) Àr svÄra att utreda och har bara en uppklarningsprocent pÄ 11% respektive 7%. Narkotikabrotten Àr dÀremot lÀttutredda dÄ de flesta har anmÀlts för innehav av polisen, Àr identifierade och bevis finns. 52% leder till personuppklaring (fÀllande dom/böter). Att satsa pÄ att utreda fler narkotikabrott fÄr till följd att polisen ser effektivare ut Àn om de skulle utreda de svÄrare botten mot personer dÀr det krÀvs teknisk bevisning och annat krÄngel.

Det Àr samtidigt ett incitament för att kÀmpa för narkotikaförbudet. Om det skulle försvinna sÄ skulle polisens personuppklarningsprocent minska med en ca en fjÀrdedel, Àven om man rÀknar med att tiden som lÀggs pÄ narkotikabrott skulle lÀggas pÄ att försöka klara upp fler stölder och brott mot personer.

Björn Fries nÀmner att Mobilisering mot Narkotika hade sett tendenser dÀr polisen griper samma missbrukare om och om igen för att fÄ bra statistik:

| â | Konsumtionsförbudet infördes 1988. Riksdagen ville att all hantering av illegal narkotika skulle vara förbjuden â Ă€ven att ha den i kroppen. Man ville ocksĂ„ göra det lĂ€ttare att upptĂ€cka nya missbrukare och erbjuda dem vĂ„rd.

Förbudet ger polisen rÀtt att utnyttja tvÄngsÄtgÀrder, som urinprovtagning, vid misstanke om narkotikabruk. Detta Àr integritetskrÀnkande, och förbudet har kritiserats för att innebÀra en kriminalisering av narkomanerna sjÀlva. Lagen kan dÀrför bara motiveras om dess positiva effekter övervÀger.

Problemet Ă€r att det finns tecken pĂ„ att lagen inte har fungerat som avsett. En studie frĂ„n Mobilisering mot narkotika visade att den ibland anvĂ€nds för att frisera polisens statistik â polisen griper och drogtestar kĂ€nda missbrukare, ibland flera gĂ„nger i veckan, för att dĂ€rigenom kunna redovisa fler uppklarade brott. SĂ„dana trakasserier Ă€r ett kvalificerat slöseri med polisens resurser. |

â |

Statistiken frÄn 2014 och 2015 visar i vilken riktning det gÄr och vilka som jagas:

| â | De senaste 20 Ă„ren har antalet arbetstimmar som lagts ner av poliser pĂ„ narkotikaĂ€renden nĂ€stan tredubblats.

... De senaste 20 Ă„ren har antalet mĂ€nniskor som misstĂ€nks för brott mot narkotikastrafflagen ökat med drygt 250 procent â och en allt mindre andel av dessa Ă€r langare. 1994 misstĂ€nktes 7.984 personer för brott mot narkotikastrafflagen och 2014 var den siffran 28.116. 1994 handlade knappt var fjĂ€rde misstanke om överlĂ„telsebrott, det vill sĂ€ga försĂ€ljning av narkotika. Förra Ă„ret var den siffran rekordlĂ„g. Bara 8 procent, drygt tvĂ„ tusen personer, misstĂ€nktes dĂ„ för langning. PĂ„ frĂ„gan om varför polisen framförallt griper dem som anvĂ€nder droger och inte dem som sĂ€ljer preparaten, svarar Liselott Jergard: â Vi fĂ„r fast de som sĂ€ljer preparaten ocksĂ„. Men procentuellt sett handlar det ju om vĂ€ldigt fĂ„ fall? â Ja, men vi har vĂ€ldigt mĂ„nga goda fall. Det bedrivs ett otroligt gott arbete, men det Ă€r utmanande och krĂ€ver resurser pĂ„ lĂ„ng sikt. Det Ă€r inte alltid vi fĂ„r de uppgifter vi behöver för att fĂ„ till en lagföring, sĂ€ger hon. Det Ă€r svĂ„rare att fĂ„ fast langare? â Ja, det Ă€r en större utmaning. ... Fram till sista september i Ă„r har 71.520 brott mot narkotikastrafflagen anmĂ€lts. 89 procent av anmĂ€lningarna, rör anvĂ€ndning och innehav â 63.944 stycken. Endast 10 procent, 6.951 stycken av anmĂ€lningarna, rör langning. ... Siffror frĂ„n Brottsförebyggandet rĂ„det, BRĂ

, som SVT tagit fram visar dessutom att en tredjedel av droganvÀndarna Äterkommer i statistiken och har lagförts för ringa narkotikabrott mer Àn en gÄng de senaste fem Ären. |

â |

2017 beskriver poliser sitt arbete som en "pinnjakt" dÀr man prioriterar lÀttuppklarade brott (narkotikabrott)[20] och pÄ grund av detta kan man visa en ökning i antalet fall som lÀmnas över till Äklagare, en siffra som pÄstÄs Äterspegla hur effektiv polisen Àr[21].

Att man jagar och straffar missbrukare istÀllet för smugglare och langare har en negativ effekt pÄ den övriga brottsstatistiken, men det verkar fÄ personer inse. Missbrukare som blir av med sitt knark eller fÄr böter för innehav/bruk kommer i hög grad att behöva begÄ brott sÄsom exempelvis nya narkotikabrott (överlÄtelse), stölder, inbrott eller rÄn för att fÄ pengar till nya droger eller betala sina böter[22]. Bland kvinnor Àr det Àven vanligt med prostitution som finansieringsmetod.

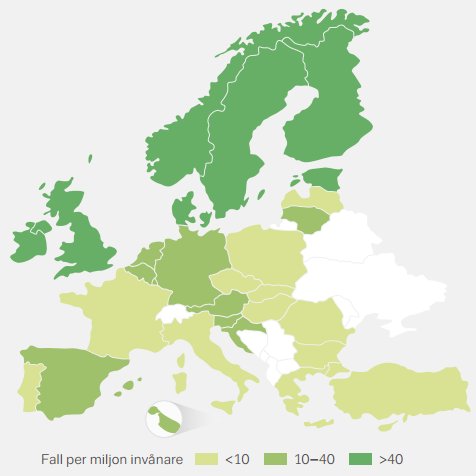

En jÀmförelse av narkotikadödligheten

Man kanske kan tro att en repressiv narkotikapolitik gör att folk knarkar mindre och dÀrmed dör fÀrre personer av narkotika Àn i lÀnder dÀr preventionen Àr inriktad pÄ att inte straffa konsumenterna. DÀrför Àr det vÀldigt intressant att göra jÀmförelser med sÄdana lÀnder.

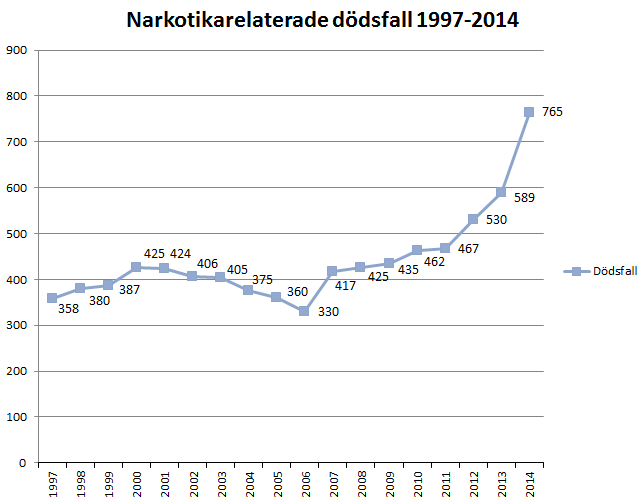

En överblick över antalet narkotikarelaterade dödsfall i Sverige de senaste Ären:

KÀlla: Data frÄn Socialstyrelsens statistikdatabas för dödsorsaker[23]

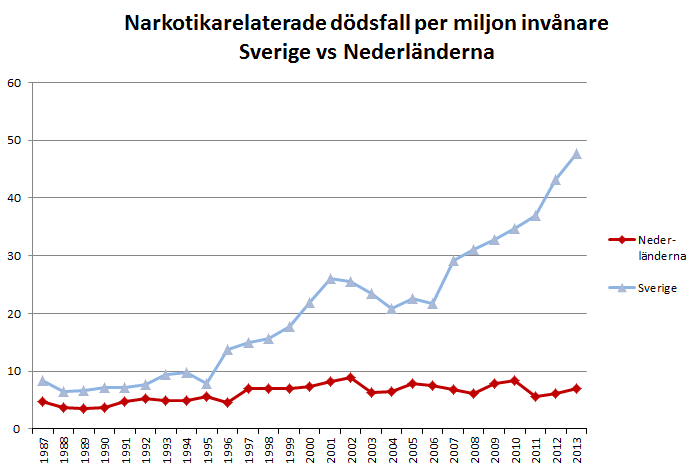

En jÀmförelse mellan trenderna gÀllande antal dödsfall i Sverige och NederlÀnderna:

HÀr ovan har vi berÀknat antalet dödsfall/miljon invÄnare med hjÀlp av officiell demografisk statistik[24][25] och dödstal frÄn EMCDDA[26].

118 personer i NederlÀnderna dog 2013 av en narkotikarelaterad orsak, motsvarande siffra för Sverige var 460 enligt EMCDDA-statistiken (siffrorna skiljer sig mot Socialstyrelsen dÄ kriterier för vad som inkluderas i databaserna skiljer sig). I skrivande stund finns inte data frÄn bÄda lÀnderna för 2014, men vi kan notera att de svenska dödsfallen ökade med 30% mellan 2013-2014[27], medan NederlÀndernas antal förmodligen fortfarande ligger stabilt.

EMCDDA visar i sin rapport frĂ„n 2015[28] att dödligheten kan anses vara mycket högre i Sverige. Narkotikainducerade dödsfall i Ă„ldersgruppen 15â64 Ă„r anges för Sverige vara 69,7 dödsfall per miljon invĂ„nare och i NederlĂ€nderna 10,2 dödsfall per miljon invĂ„nare. Dödligheten Ă€r dessutom högre i Sverige Ă€n de flesta andra europeiska lĂ€nderna[29]. Enligt socialstyrelsens senaste siffror har dödligheten nu ökat till 100,3 per miljon invĂ„nare[27].

Professor Ted Goldberg gör en jÀmförelse med antalet problematiska konsumenter mellan vÄra lÀnder:

| â | â trots avkriminalisering av cannabis, och trots tillgĂ„ng till cannabis i coffee shops och trots alla andra harm reduction-Ă„tgĂ€rder som tvĂ„ generationer hollĂ€ndare levt med sedan barnsben, visar tillgĂ€nglig statistik att antalet problematiska konsumenter per capita i NederlĂ€nderna Ă€r pĂ„ samma nivĂ„ som i Sverige. (Goldberg, 2005, s 311f) â Professor Ted Goldberg (2012)[30] |

â |

Och Mark Haden noterar att NederlÀnderna har fÀrre intravenösa brukare Àn Sverige och att Sverige har fler överdoser och missbrukare smittade med Hepatit C.

| â | The Dutch vs the Swedes

Social factors are more important indicators than criminal sanctions in determining levels of drug abuse. This conclusion is apparent in the debate between Sweden and the Netherlands. These two countries are the two extremes in Europe. The Dutch are the most liberal and the Swedes are the most repressive in their drug policies. Both countries have very low addiction rates (the Netherlands are slightly lower) in spite of their contrasting policies. Both countries are wealthy welfare states and have a high degree of social cohesion. It is predictable that they would both experience limited problems. One of the most significant differences between these two countries is the Swedes have an overdose rate which is 3 time higher than the Netherlands (1.6 vs .5 per 100,000 pop). In Amsterdam drug use is decreasing in Sweden drug use is increasing. The Netherlands have the lowest rate of drug injection in Europe. The Swedes have the highest HEP C infection rate in Europe (92% of IDUâs). The Netherlands used to be the radical amongst the Europeans and now that most of Europe is changing, Sweden is now the radical of this group. |

â |

Förklaringar till ökningen

Det hÀvdas att mÄnga lÀnder tidigare har haft olika sÀtt att föra statistik, vad som rÀknas som drogrelaterad dödsfall skiljer sig exempelvis mellan lÀnderna, och kan ge en missvisande bild[32]. Detta Àr nÄgot som förbudsföresprÄkarna menar Àr fallet för just denna jÀmförelsen, se exempelvis lÀngre ner dÀr vÄr f.d barn- och Àldreminister Maria Larsson gör den hÀnvisningen. Vad som Àr svÄrare för dessa att svara pÄ Àr varför Sveriges narkotikadödlighet genom Ären visar en stigande trend till skillnad mot NederlÀndernas, som visar en stabil nivÄ (t.o.m minskande trend för opiater)[33]. Man kan Àven notera att statistiken blivit mer homogen de senaste Ären[34]:

| â | At present, national mortality statistics are improving in most countries and their definitions are becoming more comparable, or with small differences, to the common EMCDDA definition (âSelection Bâ and âSelection Dâ). A few countries still include cases due to psychoactive medicines or non-overdose deaths, generally as a limited proportion of the total. (Part 2 of this Methodological note details definition of âdrug-related deathâ used in each Member State).

In addition, there are still differences between countries in procedures of recording cases, and in the frequency of post-mortem toxicological investigation. In some countries information exchange between GMR and SR (forensic or police) is insufficient or lacking, which compromise the quality of information. However considerable progress has been obtained during the last years in quality and reliability of information on many Member States. Direct comparisons between countries in the numbers or rates of drug-related deaths should be made with caution; but if methods are maintained consistently within a country, the trends observed can give valuable insight when interpreted together with other drug indicators. |

â |

Socialstyrelsen skriver 2016 i ett pressmeddelande[36] att ökningen av dödsfall förklaras av förbÀttrade rÀttsmedicinska analyser, hur dödsorsaksintyg registreras och kodas samt förÀndringar dÀr vissa lÀkemedel tillkommer och andra fasas ut.

Socialstyrelsens slutsatser fÄr dock hÄrd kritik av rÀttsmedicinska experter:

| â | FörĂ€ndringar som gĂ€ller kodning av dödsorsaker kan inte pĂ„verka Toxreg som enbart utgĂ„r frĂ„n rĂ€ttskemiska analyser. FörbĂ€ttrade analysmetoder som gör det möjligt att upptĂ€cka mycket lĂ„ga koncentrationer kan knappast pĂ„verka Dödsorsaksregistret, som bygger pĂ„ dödsattester, dĂ€r ansvarig rĂ€ttslĂ€kare anger vad som hade betydelse för dödsfallet. Substanser i sĂ„ lĂ„ga koncentrationer att de inte orsakat dödsfallet tas inte med pĂ„ dödsattesten. I Ă€nnu mindre grad pĂ„verkas EMCDDA:s register, som ocksĂ„ utgĂ„r frĂ„n Dödsorsaksregistret men enbart baseras pĂ„ underliggande dödsorsak, den dödsorsak som bedöms ha störst betydelse för döden.

... Majoriteten av alla narkotikarelaterade dödsfall Àr förgiftningar och förgiftningsdödsfallen har ökat kraftigt under den senaste tioÄrsperioden. ... Det resonemang som Socialstyrelsen framför, att en ökad screening skulle ha medfört en ökning av narkotikarelaterade dödsfall, innebÀr att RÀttsmedicinalverket tidigare skulle ha missat att identifiera förgiftningsfall relaterade till opioider. Detta antagande stÄr i strid med praktisk rÀttsmedicinsk erfarenhet, dÄ det i praktiken Àr ovanligt att förgiftning av en missbrukssubstans kommer som en överraskning. I stÀllet Àr den senare toxikologiskt bekrÀftade förgiftningen nÀstan alltid misstÀnkt frÄn början utifrÄn omstÀndigheterna kring dödsfallet. Om man genom ökat screening skulle ha upptÀckt förgiftningar i högre grad Àn tidigare, borde detta ha Äterspeglat sig i en motsvarande minskning av andelen dödsfall utan pÄvisad dödsorsak bland rÀttsmedicinskt undersökta dödsfall, vilket inte har skett. ... Socialstyrelsens undersökning ger inte intryck av att bygga pÄ en förutsÀttningslös analys av den ökade dödligheten som flera tidsserier indikerar. I stÀllet fÄr man intrycket av att man vill tona ned möjligheten att vi stÄr för ett allvarligt hÀlsoproblem som till viss del pÄminner om den opioidepidemi vi nu ser i USA. |

â |

Den politiska debatten kring statistiken

Beatrice Ask (BA) blir grillad om statistiken kring dödsfall i Ekots Lördagsintervju med Tomas Ramberg (TA) den 10:e december 2011:

| â | TR: - Att mĂ€nniskor dör av knark Ă€r i Sverige dubbelt sĂ„ vanligt som EU:s genomsnitt enligt dom hĂ€r siffrorna. Hur bra fungerar den hĂ€r hĂ„rda politiken dĂ„?

BA: - Den Àr vÀldigt framgÄngsrik dÀrför att den innebÀr att fÀrre mÀnniskor dras in i missbruket relativt sett och det Àr bra TR: - Om dubbet sÄ mÄnga dör, varför Àr det framgÄngsrikt? BA: - Att dö Àr inte den enda effekten som kan komma utav missbruk... TR: - Det mÄste ju vara den vÀrsta? BA: - Ja, alltsÄ, man kan sÀga sÄhÀr: Om du vill ha en liberal narkotikapolitik vilket en del förordar, dÄ kan vi tÀnka oss att man fÄr röka marijuana och hasch fritt. Det fÄr vÀldigt allvarliga skador, folk dör inte omedelbart men dom blir ganska sÄsiga i huvudet och fÄr andra medicinska problem och sociala problem, sÄ man mÄste mÀta det hÀr med tydligt bredare penseldrag Àn att bara titta pÄ dödligheten. TR: - Du menar alltsÄ att den hÀr dubbla dödligheten vi har mot EU:s genomsnitt, det Àr liksom priset man fÄr betala för att det inte Àr fler som gÄr omkring och Àr sÄsiga i huvudet? BA: - Nej, jag tycker inte att man man man kan sÀga att att det Àr det priset man fÄr betala. Det Àr naturligtvis nÄgot man mÄste arbeta med, men jag tycker inte att man kan göra som du försökte vÀnda det och sÀga det att eftersom vi har en del som anvÀnder sig av utav vÀldigt allvarliga droger eller tar överdoser sÄ skulle hela politiken vara misslyckad för man kan mÀta pÄ andra sÀtt och ser att vi har glÀdje av att vi har en restriktiv narkotikapolitik... ... |

â |

Författaren Johan Norberg reagerar pÄ dessa och andra lama ursÀkter frÄn regeringens företrÀdare:

| â | TĂ€nk er att Trafikverket hade en helt ny plan för att minska antalet döda i trafiken, och sĂ„ visar en utvĂ€rdering att antalet tvĂ€rtom fördubblades. Eller om Arbetsmiljöverket fick helt nya befogenheter för att minska arbetsplatsolyckorna, och sĂ„ fördubblas de i stĂ€llet. Till slut stĂ„r de dĂ€r med betydligt högre dödstal Ă€n omvĂ€rlden â sĂ€g 36,7 per en miljon invĂ„nare, mot 21,4 i EU i genomsnitt.

Tror ni att nĂ„got av dessa verk skulle tala om att vi har âlyckats vĂ€lâ, att âi en europeisk jĂ€mförelse har vi en jĂ€mförelsevis god situationâ, och att vi kanske till och med Ă€r âbĂ€st i vĂ€rldenâ? ... Maria Larsson förklarar nu Sveriges pinsamma placering i EU:s narkotikastatistik med att det Ă€r statistiken det Ă€r fel pĂ„. Den Ă€r inte internationellt jĂ€mförbar eftersom man rapporterar dödsfall pĂ„ olika vis. Men Ă€ven om sĂ„ skulle vara Ă€r utvecklingen i ett land över tid jĂ€mförbar, och dĂ„ har hon fortfarande en dubblering sedan 1988 att förklara. Dessutom har arbetet med att skapa gemensamma definitioner och informationsprocedurer fortskridit sĂ„ mycket att EU i alla fall tycker att det Ă€r vettigt att jĂ€mföra. Det Ă€r klart att det finns stora osĂ€kerheter, men det Ă€r bĂ€ttre att ha ungefĂ€r rĂ€tt Ă€n exakt fel. |

â |

Replik frÄn Maria Larsson, nu aningen bÀttre pÄlÀst:

| â | Norberg hĂ€nger, liksom mĂ„nga före honom, upp sin argumentation pĂ„ förekomsten av narkotikarelaterade dödsfall i Sverige. Innan jag förklarar varför det inte Ă€r ett sĂ€rskilt vettigt sĂ€tt att resonera, sĂ„ Ă€r det vĂ€l ingen, debattör eller politiker, som tar lĂ€tt pĂ„ dödsfall.

... Hur ligger det dĂ„ till med de data om narkotikarelaterade dödsfall som pekar pĂ„ att Sverige har en sĂ€rskilt dĂ„lig situation? Mitt svar Ă€r att nĂ„gra internationella jĂ€mförelser inte lĂ„ter sig göras. Vi kan inte sĂ€ga att dödsfallen ligger högt jĂ€mfört andra lĂ€nder â och att det beror pĂ„ vĂ„r narkotikapolitik. Statistiken pĂ„ omrĂ„det hĂ€rstammar frĂ„n nationella kĂ€llor, som alla Ă€r beroende av faktorer sĂ„som regler kring obduceringar, traditioner bland lĂ€kare som kodar dödscertifikaten, och flera andra faktorer. Det vi med sĂ€kerhet vet, Ă€r att enligt tillgĂ€ngliga studier, Ă€r överdödligheten för en heroinmissbrukare cirka 20 gĂ„nger högre Ă€n för normalbefolkningen. Det Ă€r en siffra som verkar lika i alla lĂ€nder dĂ€r man gjort nĂ„gon studie. Men oavsett hur vĂ„rt dödstal förhĂ„ller sig till andra lĂ€nders, vill jag sjĂ€lvfallet inte ha nĂ„got narkotikadödsfall i vĂ„rt land. I Sverige och i andra lĂ€nder finns starka krafter som vill ha en mer tillĂ„tande instĂ€llning till narkotika. Injektionsrum, heroinförskrivning och legal narkotika â Ă€r det den vĂ€gen Johan Norberg vill gĂ„? |

â |

2015 uppmÀrksammar SVT att Sverige nu tagit en andraplats i topplistan över lÀnder dÀr flest personer dör av narkotika[41]. Professorerna Börje Olsson[42] och Bengt Svensson[43]tillÄts vÀdra Äsikten att den svenska narkotikapolitiken ej Àr optimal och att man behöver fler skademinimerande ÄtgÀrder (harm reduction). SVT passade Àven pÄ att göra en enkÀtundersökning[44] dÀr riksdagspartierna fÄr delge sina Äsikter om narkotikapolitiken och deras uppfattning om varför situationen ser ut som den gör. Flera partier menar att statistiken Àr fel, man stÀller sig frÄgande till andra lÀnders egna statistik och menar att Sverige inkluderar narkotikabelagd medicin i siffrorna.

Faktum kvarstÄr: De statistiska metoderna har blivit mer lika varandra, att hÀnvisa till missvisande siffror blir svÄrare och svÄrare. Huruvida heroindödligheten Àr högre Àn för normalbefolkningen har inte med sakfrÄgan att göra. Skulle man istÀllet frÄga sig varför heroinister dör sÄ handlar det mer om osÀker kvalitet som leder till överdoser, smittsamma sjukdomar och elÀndiga sociala förhÄllanden till följd av missbruket och samhÀllets missriktade insatser (straff istÀllet för vÄrd) Àn drogen i sig. Det Àr dÀrför man gör hela jÀmförelsen, ser man hela problemet som ett hÀlsoproblem snarare Àn ett straffrÀttsligt problem och lÀgger insatserna pÄ skadeprevention sÄ leder det till att fÀrre personer dör. Nolltoleransen lyckas inte bÀttre med detta.

Debattklimatet

Ted Goldberg beskriver Sveriges historiska syn pÄ narkotikafrÄgans bÄda lÀger och debattklimatet:

| â | ARE THERE ONLY TWO CHOICES?

Part of the reason so many people are advocating some form of legalisation is to be found in the polarisation which has marked the drug debate. The alternatives have been reduced to two: either you support the current drug policies or you're a 'drug liberal'. People have been led to believe that there are no other alternatives. In Sweden, for instance, one of the leading voices in the drug debate, Nils Bejerot, writes: After 12 years of debate there are still some points to be settled. How prevention and narcotics policy in general shall be drawn up (strict, restrictive and consistent or lax, liberal and inconsistent) ... (Bejerot, 1979, p. 8). That drug policy could be formulated from a wider range of alternatives appears to be out of the question. When an increasing number of people feel that drug policies have failed, and at the same time have been led to believe that the only alternative is legalisation, what remains other than to be for legalisation? Presumably 'either/or-thinking' on drug policy is based on the fear that any questioning of current policy will weaken resistance to narcotics and lead to more drug misuse. In Sweden, anyone who questions the Swedish model runs the risk of being the target of personal attack. Critics are threatened, scorned, risk losing their jobs, etc. Sometimes the attacks are extended to a critic's family. For instance, two leading voices in the narcotics debate had the following to say about critics of some of Sweden's treatment centres: a critical social worker was described as 'a deplorable wreck', and a journalist/researcher was characterised as being extremely cold and insensitive. Concerning a third critic readers are informed that she lives together with 'one of the left wing party's most drug and treatment liberal profiles' (Westerberg and Andersson, 199 1, p. A4). Perhaps to a non-Swedish audience these comments might appear more childish than abusive. But in Sweden language tends towards understatements, and in the context of Swedish culture these comments are very drastic and cutting. Such statements could possibly be excused if they were spoken 'in the heat of battle' and later mollified, but the authors of the article referred to above chose to publish it a second time about a year after it first appeared. Few people wish to expose themselves and their families to this kind of abuse. Many Swedes who have a different understanding of narcotics have permitted themselves to be silenced and thereby left the field open for either/or- thinking. Defenders of the Swedish model have increasingly had the field to themselves. The number of people who were openly critical diminished and those who continued to speak out experienced increasing difficulty in making their voices heard. The relatively few who were not silenced were, in Thomas Mathiesen's words, 'defined out', that is, considered to belong to the fringe and therefore there is no reason to discuss what they have to say (see Mathiesen, 1980, chapters 5 and 6). As critical ideas have not been taken seriously, the only two alternatives remaining have been those defined by adherents of the Swedish model; i.e. either accept the country's current drug policy or legalise narcotics. |

â |

| â | One of the major arguments proposed within the control and sanction (prohibition) strategy in the 1960s was that, even though Sweden had fared reasonably well compared to many other countries, alcohol had still caused serious problems, and society would have been far better off without it. However, it was not possible to eliminate alcohol entirely so the nation was obliged to choose the ânext best policyâ â reducing alcohol-related harm to the extent possible. The new illicit drugs were not already rooted in Swedish culture, however, and it was argued that it would be utter madness to let them gain a foothold in the country. Proponents of prohibition believed that narcotics could be successfully kept out of society by acting resolutely and conveying a clear and consistent message to youths that these drugs are dangerous and as such, not tolerated. In response to the perceived threat, prohibitionists called for new laws, stringent controls, increased penalties, and the suppression of opposing points of view.

No censorship laws were passed, but both radio and TV were public broadcasting monopolies at the time and opponents of prohibitionist policies were simply not given air time. Even the editors of privately owned newspapers and magazines acted as it were a public duty to combat the spread of drugs by not giving âfalse prophetsâ a chance to confuse children. As late as 1998, this position was proclaimed in an editorial in Dagens Nyheter,the most prestigious daily newspaper in the country: â[Swedish] Narcotics policy is built upon instilling the belief that all use of narcotics is a serious breach of norms. When this policy is put into question it brings a strong reaction because without wide support from the general public the policy cannot be effectiveâ (Friborg, 1998, p. A2). Until that time, the fear of narcotics was so great in Sweden that questions of free speech and censorship were not even considered issues in conjunction with illicit drugs (as opposed to just about any other issue). The author wrote a rejoinder to the aforementioned editorial (Goldberg, 1998, p. A2), but this informal censorship had already been abandoned three months earlier when 12 Swedish intellectuals signed an open letter to United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan questioning UN drug policies. This letter received a great deal of attention, and the Swedish signatories were given the opportunity to express their views in the mass media. Consequently, June 1998 may be seen as marking the beginning of a renewed public debate on Swedish drug policy. The aforementioned editorial can be seen as the last gasp of the old regime. Since then, there has been a more open debate in all segments of the Swedish mass media. |

â |

LÀsvÀrt

- Tim Boekhout van Solinge (1997): The Swedish Drug Control System - An in-depth review and analysis av CEDRO DjupgÄende analys av den svenska narkotikapolitiken. Allt frÄn historia till olika aktörer. Mycket lÀsvÀrd för den som vill sÀtta sig in i narkotikapolitiken.

- Ted Goldberg (2004): The Evolution of Swedish Drug Policy Intressant genomgÄng av den svenska drogpolitiken av Ted Goldberg, professor sociologi. En man som en har en hög förestÄelse för narkotikasituationen och vad man bör göra Ät den.

- Christie, N & Bruun, K. (1985): Den gode fiendenâ narkotikapolitik i Norden. Kristianstad, Universitetsforlaget

- Ted Goldberg (2005): SamhÀllet i narkotikan. Stockholm, Academic Publishing of Sweden.

- Börje Olsson (1994): Narkotikaproblemets bakgrund. Stockholm, CAN.

- Henrik Tham m fl. (2003):Forskare om narkotikapolitiken Kriminologiska institutionen, Stockholms universitet.

- RFHL (1998): Svensk Narkotikapolitik - Kritik och motkritik

- Lauri Hellström (2012): Zero Tolerance and Harm reduction, International drug norms in practice, A case study of Sweden and Portugal

KĂ€llor

- â Metro 2012-03-21: Sveriges knarkpolitik sĂ€mst, inte bĂ€st

- â The Swedish Drug Control System - An in-depth review and analysis av CEDRO

- â 3,0 3,1 Swedenâs Successful Drug Policy: A Review Of The Evidence (Costa, 2007)

- â Swedish Drug Policy: A Successful Model? (Tham, 1998)

- â Drugnews 2006-09-07: FN hyllar svensk narkotikapolitik

- â Svensk bedömning av multilaterala organisationer: FN:s organ mot brott och narkotika, UNODC

- â Sveriges internationella engagemang pĂ„ narkotikaomrĂ„det (SOU 2011:66) sid 85.

- â Transform Drug Policy Foundation: Sweden's drug policy: A reality check (Rolles, 2007).

- â Looking at the UN, smelling a rat - A comment on âSwedenâs succesful drug policy: a review of the evidenceâ (Cohen, 2006)

- â Dressed for Success? A critical review of âSwedenâs Successful Drug Policy: A Review of the Evidenceâ (Olsson, 2009)

- â What Can We Learn From Swedenâs Drug Policy Experience? (Hallam, 2010)

- â Ted Goldberg - The Evolution of Swedish Drug Policy (2004)

- â SVT 2015-11-11: FN: Sveriges narkotikapolitik lever inte upp till mĂ€nskliga rĂ€ttigheter

- â Skolverket 2013: Undervisning om alkohol, narkotika, dopning och tobak (ANDT) â en praktiknĂ€ra litteraturgenomgĂ„ng

- â SBU Rapport nr 243 2015: Att förebygga missbruk av alkohol, droger och spel hos barn och unga - En systematisk litteraturöversikt

- â SVT: 2015-11-11: âVerkningslöst" arbete mot knark i skolan

- â BRĂ : Handlagda brott PreliminĂ€r statistik för första halvĂ„ret 2015 samt prognoser för helĂ„ret 2015

- â Aftonbladet 2010-08-09: Alliansen â populister i sin narkotikapolitik

- â SVT 2015-11-11: Fler grips för narkotikabruk â men langarna kommer undan

- â SvD 2017-06-14: PoliskĂ€llor: Enkla brott prioriteras i jakt pĂ„ resultat

- â SvD 2017-10-10: Narkotika- och trafikbrott lyfter polisresultat

- â SVT 2015-11-11: Begick fler brott för att betala sina böter

- â Socialstyrelsen: Statistikdatabas för dödsorsaker

- â Statistiska CentralbyrĂ„n (SCB)

- â Statistics Netherlands (CBS)

- â EMCDDA Data and statistics: Overdose deaths, Trends, National definition, Number of deaths, Total

- â 27,0 27,1 Socialstyrelsen Dödsorsaker 2014 â Causes of Death 2014

- â EMCDDA: Europeisk narkotikarapport 2015: Trender och utveckling

- â EMCDDA: Figure DRD-7. Mortality due to drug-induced deaths among all adults (15 to 64 years) in European countries for the most recent year reported

- â Vad hĂ€nder om vi legaliserar narkotika? (Ted Goldberg, Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift nr 1, 2012)

- â A Public Health Approach to Illegal Drugs (Haden, 2002)

- â Ăr det möjligt att jĂ€mföra statistik över narkotikarelaterade dödsfall mellan olika lĂ€nder? (Fugelstad)

- â EMCDDA: National report 2011: Netherland

- â EMCDDA: Drug-related deaths and mortality (DRD) (Aktuell)

- â EMCDDA 2011: Drug-related deaths and mortality (DRD)

- â Socialstyrelsen. Pressmeddelande 2016-02-29: MĂ„nga orsaker bakom narkotikadöd

- â DN Debatt 2016-04-03: Faktisk ökning av antalet narkotikadödsfall mörkas

- â Ekots Lördagsintervju (SR) den 10:e december 2011. Lyssna frĂ„n 15:45

- â Johan Norberg om Narkotikapolitik: Maria Larssons krig mot narkotika Ă€r ideologiskt

- â Maria Larsson om Narkotikapolitik: Johan Norbergs pĂ„stĂ„enden om mig Ă€r oförskĂ€mda

- â SVT 2015-06-04: Narkotikadödligheten i Sverige nĂ€st högst i EU

- â SVT 2015-06-04: âEn politik som inte Ă€r i takt med tidenâ

- â SVT 2015-06-04: Professorn om enkĂ€ten â förvĂ€ntade mig mer konkreta förslag

- â SVT 2015-06-04: Trots dödligheten â politikerna nöjda med drogpolitiken hela enkĂ€ten som pdf

- â The Swedish Narcotics Control Private Model - A Critical Assessment (Goldberg)

- â The Evolution of Swedish Drug Policy (Goldberg, 2004)

Detta Àr bara en liten del av Legaliseringsguiden. Klicka pÄ lÀnken eller anvÀnd rullistan nedan för att lÀsa mer om narkotikapolitiken, argumenten för en avkriminalisering & legalisering, genomgÄngar av cannabis pÄstÄdda skadeverkningar, medicinska anvÀndningsomrÄden och mycket mera. Det gÄr Àven att ladda ner hela guiden som pdf.

Sidan Àndrades senast 10 oktober 2017 klockan 14.34.

Den hÀr sidan har visats 19 053 gÄnger.