|

MAGISKA MOLEKYLERS WIKI |

Cannabis och beroende

Inneh├źll

M├źnga h├żvdar att man inte kan bli beroende av cannabis. Det ├żr givetvis fel. Man kan bli beroende av cannabis, precis som man kan bli beroende de flesta andra olagliga och lagliga droger, samt av mat, sex, spel eller datorspel[1][2] eller andra aktiviteter som utl├Čser sm├ź dopaminbel├Čningar, skapar tillfredsst├żllelse, g├Čr att man vill n├ź den igen, men vid f├Čr t├żta upprepningar nedregleras dopaminsystemet s├ź att man upplever en saknad n├żr aktiviteten inte kan utf├Čras och att bel├Čningen inte k├żnns lika intensiv som tidigare. Cannabis ├żr med andra ord inget undantag fr├źn alla saker en m├żnniska kan bli beroende av.

Det finns ett psykiskt beroende som visar sig genom att man l├żngtar efter att vara h├Čg. Beroendet kan komma sakta och det ├żr inte s├żkert att man omedelbart m├żrker att man har blivit psykiskt beroende. R├Čker man dagligen s├ź kommer man att v├żnja sig vid att vara h├Čg under vissa tider eller tillf├żllen p├ź dagen. N├żr man sedan slutar s├ź kommer det psykiska beroendet g├Čra att man i samband med dessa tillf├żllen vill vara h├Čg. Har man exempelvis som vana att r├Čka varje kv├żll s├ź kommer man att vilja r├Čka cannabis p├ź kv├żllarna. Brukar man r├Čka innan man ska kolla p├ź en film s├ź kommer man vilja r├Čka innan man ska kolla p├ź film, osv. Situationerna d├żr man brukar vara p├źverkad kommer den f├Črsta tiden under ett uppeh├źll d├żrmed att medf├Čra en viss k├żnsla av att n├źgonting saknas. Att sluta r├Čka cannabis handlar fr├żmst om att k├żmpa mot det psykiska beroendet. Att inte falla f├Čr frestelsen att r├Čka igen f├Čr att ŌĆØg├Čra situationen mer njutbar eller intressantŌĆØ.

Psykiska abstinenssymptom som uppst├źr n├żr man som kronisk cannabisr├Čkare abrupt slutar ├żr bl.a:

- Irritation. Ofta p├ź grund av sm├źsaker. Det ├żr inte lika l├żtt att finna "peace-and-love-attityden".

- S├Čmnl├Čshet. Fr├żmst om man har som vana att r├Čka innan s├żngdags. Generellt s├ź sover man inte lika djupt

- Man dr├Čmmer mycket n├żr man sover. Mardr├Čmmar eller "konstiga" dr├Čmmar f├Črekommer.

- Rastl├Čshet. Det blir helt pl├Čtsligt mycket tid ├Čver n├żr man inte spenderar flera timmar om dagen med att vara h├Čg.

- Minskad aptit. Inte s├ź konstigt d├ź cannabis ├Čkar aptiten.

Abstinensen ├żr v├żrst den f├Črsta veckan och klingar sedan av under ett par veckor. Vissa symptom som dr├Čmmar och irritation kan kvarst├ź l├żngre tid.

Det fysiska beroendet ├żr sv├źrdefinierat d├ź cannabisabstinens inte inneb├żr samma fysiska komplikationer som f├Čr t.ex alkohol d├żr kroppen blivit beroende av drogen och det kan vara direkt livsfarligt med ett omedelbart stopp[3][4]. Man har letat efter abstinenssymtom, men de som finns ├żr mycket milda. M├źnga cannabisr├Čkare anser att fysiska symtom exempelvis rastl├Čshet och svettningar ├żr effekter fr├źn det psykiska beroendet eftersom det n├żstan enbart uppst├źr n├żr man t├żnker p├ź att r├Čka, inte n├żr man ├żr p├ź arbetet/skolan eller d├ź man deltar i andra aktiviteter eller sammanhang d├żr man inte brukar vara h├Čg.

Personer som har st├Črst problem med att avbryta ett beroende ├żr oftast kroniska r├Čkare som r├Čker flera gram om dagen och har gjort det under l├żngre tid. Dessa faktorer ger h├Čgre grad av abstinenssymptom, vilket f├Črklarar en h├Čgre ├źterfallsrisk. Flera forskare h├żnvisar till att en nedtrappning av dosen/frekvensen en tid innan det definitiva stoppet kan minska graden av abstinens.

Det som ├żr viktigt att po├żngtera ├żr att beroendet ├żr v├żldigt l├żtt att ta sig ur, j├żmf├Črt med m├źnga andra droger.

L├żs ├żven Magiska Molekylers guide om Hur man slutar r├Čka cannabis.

Argument fr├źn f├Črbudsf├Črespr├źkare

Jan Ramstr├Čm

Jan Ramstr├Čm om missbruk och beroende:

| ŌĆ£ | Cannabismissbruk kan ├Čverg├ź till cannabisberoende (dependence) som karakteriseras av tre av f├Čljande sju kriterier:

Till beroendet ├żr allts├ź kopplat ett abstinenssyndrom som vid f├Črs├Čk att sluta yttrar sig i abstinenssymtom. Symtomen kommer efter 1ŌĆō2 dygn, n├źr en topp efter 2ŌĆō4 dagar och klingar av p├ź 2ŌĆō3 veckor. Vanliga symtom ├żr rastl├Čshet, ilska, irritabilitet, minskad aptit/viktned-g├źng, nervositet/├źngest och s├Čmnsv├źrigheter. Andelen anv├żndare/missbrukare av cannabis som blir beroende har i olika unders├Čkningar visat sig v├żxla betydligt men ├żr genomsnittligt f├Črv├źnansv├żrt h├Čg. Av personer som r├Čker n├źgon g├źng utvecklar 10 procent under n├źgon period i livet beroende. Den cannabisberoende har sv├źrigheter att sluta med preparatet, en f├Črh├Čjd risk att drabbas av skadeeffekter av cannabisr├Čkningen men ocks├ź en f├Črh├Čjd risk att g├ź ├Čver till andra illegala droger |

ŌĆØ |

Om abstinens:

| ŌĆ£ | "Trots kliniska iakttagelser av tecken p├ź beroende inklusive abstinenssymtom tog det ganska l├źng tid att verkligen visa att cannabisr├Čkare utvecklar inte bara missbruk utan ocks├ź beroende. Ett relativt stort antal experimentella f├Črs├Čk genomf├Črdes (man gav cannabis till f├Črs├Čkspersoner under viss tid varefter effekten av upph├Črd tillf├Črsel studerades) f├Čr att eventuellt kunna visa om det f├Črekom tolerans- och/eller abstinensbesv├żr. Inledningsvis lyckades detta inte. Ofta, bland annat av etiska sk├żl, anv├żnde man orealistiskt l├źga doser och korta unders├Čkningsperioder (Hollister, 1986). N├żr Jones och Benowitz (Jones, 1983) gav betydligt h├Čgre och t├żtare doser under en 3-veckorsperiod, uppvisade f├Črs├Čkspersonerna en viss toleransutveckling och ett abstinenssyndrom mycket likt det som kan iakttas i klinisk verksamhet.

Senare har man gjort rader av systematiska iakttagelser och studier som st├Čdjer den kliniska bilden och de experimentella unders├Čkningarna. Beroende utvecklas vid l├źngvarig och frekvent anv├żndning (Miller & Gold, 1989; Gable 1993,Comton et al 1990). Man registrerade ocks├ź abstinenssymtom. En l├żngre tids frekvent anv├żndning av cannabis ger abstinensbesv├żr n├żr missbruket avbryts. Vanliga symtom ├żr s├Čmnsv├źrigheter, oro, irritabilitet och ibland svettningar, l├żtt illam├źende, darrighet och viktnedg├źng (Comtom, et al., 1990). Inte minst s├Čmnsv├źrigheterna kan bli besv├żrande och orsakar ofta ├źterfall hos den som f├Črs├Čker sluta. Besv├żrens intensitet ├żr beroende av dos, frekvens och missbrukets varaktighet (Comton, et al., 1990, Duffy & Milin, 1996; Crowley, et al., 1998; Haney, et al., 1999). Det har ocks├ź publicerats rapporter d├żr man beskriver abstinenssymtom av ett allvarligare slag, framf├Čr allt i form av psykotiska symtom inom den manodepressiva sf├żren (Teitel, 1971; Rohr, et al., 1989)." |

ŌĆØ |

Om forskningen fr├źn A.J. Budneys och hans medarbetare:

| ŌĆ£ | Om abstinenssyndromet:

Abstinenssymtom: Vanligt f├Črekommande:

Mindre vanliga symtom:

Sammanfattningsvis ger cannabis upphov till beroende och ett abstinenssyndrom som omfattar k├żnslom├żssiga och beteendem├żssiga st├Črningar. Det r├Čr sig om ett signifikant abstinenssyndrom som dock ├żr mindre utpr├żglat ├żn vid heroin-, alkohol- och kokainberoende (Budney A.J. 2006)." |

ŌĆØ |

Pelle Olsson

Pelle Olsson skriver om cannabisberoende i "8 myter om cannabis":

| ŌĆ£ | Beroende

Precis som alla andra sinnesf├Čr├żndrande droger och nikotin ├żr cannabis beroendeframkallande. Cannabisens f├Črsvarare brukar erk├żnna att det kan ge ett ŌĆØpsykisktŌĆØ beroende, men d├ź har man inte f├Črst├źtt att beroende ├żr en diagnos som st├żlls n├żr en rad kriterier ├żr uppfyllda. D├żr ing├źr bland annat abstinenssymtom (vilka ofta uppst├źr f├Črst efter 1ŌĆō2 dagars uppeh├źll), ├Čkad tolerans och att allt mer tid ├żgnas ├źt missbruket. Cirka 10 procent av alla som r├Čker cannabis blir n├źgon g├źng beroende. |

ŌĆØ |

Pelle Olsson raljerar om att vi "f├Črsvarare" erk├żnner ett psykiskt beroende men inte f├Črst├źr beroendets definition. Man f├źr tolka lite vad han egentligen p├źst├źr d├ź det ├żr v├żldigt luddigt. Kriterierna uppfylls f├Čr att definiera cannabisberoende som just ett beroende, abstinensen ├żr i sig en definition av fysiskt beroende. Men faktum kvarst├źr; det fysiska beroendet fr├źn cannabis ├żr minimalt och beroendet ├żr fr├żmst psykiskt. Det ├żr viktigt att komma ih├źg n├żr man j├żmf├Čr med andra droger eller bed├Čmer konsekvenserna och betydelsen av ett cannabisberoende eftersom effekterna av fysiskt/psykiskt beroende ├żr avg├Črande f├Čr allvarlighetsgraden.

Mobilisering mot narkotika

Ett faktablad fr├źn Mobilisering mot narkotika (Regeringen Perssons propagandaorgan) anger att 1/10 blir beroende av cannabis, och det sker flera ├źr efter att personen b├Črjat r├Čka. Beroendet inneb├żr att man kommer att h├źlla p├ź med s.k "tv├źngsm├żssigt upprepande av cannabisrelaterade aktiviteter", vad det nu kan inneb├żra. ├är det att spela Bob Marley och g├ź omkring i kl├żder med rastaf├żrger tro?

| ŌĆ£ | ├är cannabis beroendeframkallande?

Cannabisberoendet uppfyller alla de vedertagna diagnostiska kriterierna f├Čr drogberoende, bl.a. tolerans, dos├Čkning, abstinenssymtom, att drogmissbruket blir viktigare ├żn andra aktiviteter samt problem med att styra konsumtionen. Tolerans p├źvisades till exempel i en unders├Čkning d├żr f├Črs├Čkspersonerna ?ck cannabis och deras subjektiva rusupplevelse v├żrderades under fyra dagar med samma dos. Till och med under denna korta tidsrymd avtog ruset. N├żr tolerans har byggts upp leder ett avbrott till en rad olika abstinenssymtom, bl.a. ├źngest, s├Čmnsv├źrigheter, darrningar, retlighet och aggressivitet. Kombinationen av dessa symtom g├Čr det sv├źrt f├Čr missbrukaren att sluta med sitt missbruk eller f├ź det under kontroll. ... Cannabisberoendet kan s├żgas best├ź av ?era kliniska syndrom, d├żribland st├Črningar i sj├żlslivet i form av tv├źngstankar; beteenderubbningar, t.ex. tv├źngsm├żssigt upprepande av cannabisrelaterade aktiviteter; samt en cannabisframkallad neuroadaptation som leder till fysiologiskt beroende, vilket bland annat yttrar sig i en subjektiv k├żnsla av att samma cannabisdos som tidigare har mindre effekt. Det sista fenomenet kan ocks├ź yttra sig som abstinenssymtom efter en l├żngre tids dagligt eller n├żstan dagligt cannabisbruk. Epidemiologiska studier ger vid handen att av dem som n├źgon g├źng anv├żnder cannabis blir 1-3 procent beroende inom 1-2 ├źr efter det f├Črsta anv├żndningstillf├żllet. Det ?nns uppgifter som tyder p├ź att det kan ta upp till 7-8 ├źr fr├źn det f├Črsta anv├żndningstillf├żllet innan en person blir fast i drogberoendet. Med andra ord, om n├źgon skall bli beroende av cannabis tar processen normalt h├Čgst 7-8 ├źr och oftast inte mer ├żn 4-5 ├źr efter det f├Črsta anv├żndningstillf├żllet. Detta kan j├żmf├Čras med kokain, som ├żr mycket snabbverkande. Ca 5 procent av missbrukarna blir beroende inom 1-2 ├źr efter det f├Črsta anv├żndningstillf├żllet. D├żrefter minskar risken f├Čr att bli beroende. F├Čr att s├żtta dessa siffror i sitt sammanhang kan man j├żmf├Čra med n├źgra andra vanebildande substanser. En av tre tobaksr├Čkare blir beroende. 1 av 4-5 heroinmissbrukare l├Čper risk att bli beroende. Siffran f├Čr psykedeliska droger ├żr 1 av 20, f├Čr alkohol 1 av 7-8 och f├Čr cannabis 1 av 9-11. |

ŌĆØ |

Thomas Lundqvist

Thomas Lundqvist har m├źnga egna tolkningar och definitioner, som dessutom varierar ├Čver tiden. Ett "tungt missbruk" verkar vara n├źgot som bara drabbar 1.6% av alla som n├źgon g├źng r├Čker cannabis, samtidigt ├żr ett "l├źngtidsmissbruk" definierat i en skrift som "1-4 ggr/m├źnad i tv├ź ├źr"[8] vilket resten av forskarv├żrlden skulle klassa som sporadisk/l├źg konsumtion.

| ŌĆ£ | Diagnosen cannabisberoende inneb├żr att en individ trots upplevande av en m├żngd beteendem├żssiga, kognitiva, perceptuella och emotionella symptom sammanh├żngande med missbruk av cannabis forts├żtter att anv├żnda cannabis. F├Črekommer hos ca. 10 % av anv├żndarna. ŌĆö Cannabis, beroende och behandling av Thomas Lundqvist[9] |

ŌĆØ |

| ŌĆ£ | Thomas Lundqvist ritar upp en enkelt diagram p├ź den whiteboardtavla som han brukar anv├żnda f├Čr att f├Črklara saker och ting f├Čr sina klienter.

- Om hundra personer testar cannabis s├ź kommer bara tjugo av dem r├Čka de fem g├źnger som i genomsnitt beh├Čvs f├Čr att f├ź en positiv effekt. Av dessa tjugo g├źr 8-10 procent in i ett tungt missbruk. Det betyder att 1,6 procent av alla som n├źgon g├źng pr├Čvar blir tunga narkomaner. Av tusen personer som tester blir det 16 missbrukare. De h├żr talen g├źr igen i flera stora unders├Čkningar. - De flesta slutar allts├ź av sig sj├żlva, forts├żtter Lundqvist, ofta d├żrf├Čr att de m├żrker att det inte riktigt fungerar f├Čr dem n├żr de har r├Čkt. Men ju fler individer som testar cannabis, desto fler kommer att forts├żtta och desto fler kommer att bli tunga missbrukare. |

ŌĆØ |

Det enkla diagrammet ├żr f├Črmodligen detsamma som f├Črekommer i ett flertal presentationer av Lundqvist (se exempelvis sidan nio i presentationen fr├źn 2011[9]). Vad som hade r├Čkts n├żr det togs fram, eller vad man m├źste r├Čka f├Čr att f├Črst├ź den l├żmnar vi till l├żsarna...

Haschboken

I Haschboken (upplagan fr├źn 1989) kan man l├żsa om n├źgra "myter" som cannabisr├Čkare har, samt motargumenten mot dessa:

| ŌĆ£ | "Man blir inte beroende av hasch"

Jo, m├źnga behandlare menar att det ├żr minst lika sv├źrt att bryta ett intensivt haschmissbruk som p├źg├źtt under en l├żngre tid som m├źnga andra sv├źra drogberoenden s├źsom exempelvis alkoholism och heroinism. |

ŌĆØ |

Observera: MINST lika sv├źrt att sluta med som alkohol och heroin...

Definitioner av beroende och missbruk

DSM-IV och DSM-V

Enligt diagnostikverktyget DSM-IV s├ź definierar man missbruk och beroende n├żr ett (f├Čr missbruk) eller tre (f├Čr beroende) kriterier n├źs inom en 12-m├źnaders period:

| ŌĆ£ | DSM-IV Substance Abuse Criteria:

Substance abuse is defined as a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

Note: The symptoms for abuse have never met the criteria for dependence for this class of substance. According to the DSM-IV, a person can be abusing a substance or dependent on a substance but not both at the same time. DSM-IV Substance Dependence Criteria: Substance dependence is defined as a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by three (or more) of the following, occurring any time in the same 12-month period:

|

ŌĆØ |

I den femte upplagan av DSM (DSM-V) fr├źn 2013 s├ź har man ├żndrat definitionerna av det som vi i svenskan ├Čvers├żtter till beroende och missbruk. Nu har man ist├żllet termer som mer skulle ├Čvers├żttas till grader av "cannabisbruksproblem".

| ŌĆ£ | Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. Each specific substance (other than caffeine, which cannot be diagnosed as a substance use disorder) is addressed as a separate use disorder (e.g., alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, etc.), but nearly all substances are diagnosed based on the same overarching criteria. In this overarching disorder, the criteria have not only been combined, but strengthened. Whereas a diagnosis of substance abuse previously required only one symptom, mild substance use disorder in DSM-5 requires two to three symptoms from a list of 11. Drug craving will be added to the list, and problems with law enforcement will be eliminated because of cultural considerations that make the criteria difficult to apply internationally.

In DSM-IV, the distinction between abuse and dependence was based on the concept of abuse as a mild or early phase and dependence as the more severe manifestation. In practice, the abuse criteria were sometimes quite severe. The revised substance use disorder, a single diagnosis, will better match the symptoms that patients experience. Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with ŌĆ£addictionŌĆØ when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. |

ŌĆØ |

| ŌĆ£ | "The term dependence is misleading, because people confuse it with addiction, when in fact the tolerance and withdrawal patients experience are very normal responses to prescribed medications that affect the central nervous system,ŌĆØ said Charles OŌĆÖBrien, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Substance-Related Disorders Work Group. ŌĆ£On the other hand, addiction is compulsive drug-seeking behavior which is quite different. We hope that this new classification will help end this wide-spread misunderstanding.ŌĆØ ŌĆö The American Psychiatric Association[14] |

ŌĆØ |

Kriterierna f├Čr Cannabis use disorder:

| ŌĆ£ | A problematic pattern of cannabis use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least 2 of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

ŌĆö DSM-IV[15] |

ŌĆØ |

I en amerikansk studie fr├źn 2015[16] ber├żknar man att 2.5% har uppfyllt dessa kriterierna under det senaste ├źret och 6.3% under sin livstid. De hade i genomsnitt anv├żnt cannabis 225 respektive 274 dagar/├źr.

I DSM-V introducerar man ├żven diagnosen "Cannabis Withdrawal", dvs abstinenssymptom. Det har var efterfr├źgat en l├żngre tid fr├źn vissa forskare (vi kommer till det l├żngre ner).

| ŌĆ£ | Cannabis Withdrawal

ŌĆö DSM-V[15] |

ŌĆØ |

WHO

Enligt WHO:s tolkning av ICD-10[17][18] skall minst tre av f├Čljande kriterier ha uppfyllts under det senaste ├źret f├Čr att definiera ett beroende:

- Starkt sug eller tv├źng att ta drogen

- Sv├źrigheter att hantera konsumtionen, att sluta eller kontrollera frekvensen

- Abstinenssymptom

- Tolerans├Čkning har skett, h├Čgre doser beh├Čvs f├Čr att n├ź samma niv├ź av p├źverkan

- Ett minskat intresse att ├żgna sig ├źt alternativa n├Čjen eller intressen p.g.a anskaffande och anv├żndande av drogen eller avt├żndning

- Konsumtionen forts├żtter trots klara bevis f├Čr skadliga fysiska eller psykiska effekter

Forskning om cannabisberoende

Det har under m├źnga ├źrtionden r├źdit stor os├żkerhet kring mekanismerna bakom beroendet. Under 1980-talet uppt├żckte man cannabinoidreceptorerna och att THC band till dessa. Det har sedan dess f├Črekommit m├źnga teorier kring aktivering av dopamin och opiatreceptorer[19] som bevisats och motbevisats om vartannat. Studier med f├Črs├Čksdjur visade inte i tillr├żckligt h├Čg grad att djuren har valt att b├Črja sj├żlvadministrera THC, vilket ocks├ź gjorde att forskarna hade det sv├źrt att bevisa beroendepotentialen. Hos m├żnniskor har man dock visat att man v├żljer THC framf├Čr placebo, och gr├żs med h├Čgre THC-halt f├Čredras[20].

Det nuvarande forskningsl├żget ├żr att cannabis p├źverkar bel├Čningssystemet genom en annan mekanism ├żn andra droger, men resultatet ├żr snarlikt eftersom dopaminhalterna f├Čr├żndras i omr├źdena av hj├żrnan som f├Črknippas med bel├Čningssystemet. Man upplever ett sug efter drogen och en bel├Čning n├żr man tar den[21][20][22]. Cannabinoider modulerar det mesolimbiska dopaminsystemet och dopaminniv├źerna minskar under cannabisabstinensen[23].

Hur m├źnga blir beroende?

En l├źngtidsstudie fr├źn 1991[24] med inriktning p├ź ungdomar fr├źn USA p├źvisade att beroendegraden var ganska l├źg. 77% av alla i "high school" hade anv├żnt cannabis, men 74% av dessa anv├żndare hade inte anv├żnt cannabis under det senaste ├źret och 84% hade inte anv├żnt drogen under den senaste m├źnaden.

Flera k├żllor anger att 10% av cannabisr├Čkarna blir beroende (se ├żven Ramstr├Čm, Olsson, Lundqvist, Mobilisering mot Narkotika m.m. som citeras l├żngre upp):

| ŌĆ£ | The Institute of Medicine Report (1999) suggested that 9% of those who ever used cannabis become dependent (as defined by the DSM-IV criteria); this compared with dependency risks of 32% for tobacco, 23% for heroin, 17% for cocaine, and 15% for alcohol. ŌĆö The Science of Marijuana av Professor Leslie L. Iversen (2001) |

ŌĆØ |

| ŌĆ£ | A variety of estimates have been derived from U.S. studies in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which defined cannabis use and dependence in a variety of ways. These studies suggested that between 10 and 20 per cent of those who have ever used cannabis, and between 33 and 50 per cent of those who have had a history of daily cannabis use, showed symptoms of cannabis dependence (see Hall, Solowij & Lemon, 1994). A more recent and better estimate of the risk of meeting DSM-R.III criteria for cannabis dependence was obtained from data collected in the National Comorbitity Study (Anthony, Warner & Kessler, 1994). This indicated that 9 per cent of lifetime cannabis users met DSM-R-III criteria for dependence at some time in their life, compared to 32 per cent of tobacco users, 23 per cent of opiate users and 15 per cent of alcohol users ŌĆö Hall (1999)[25] |

ŌĆØ |

En studie fr├źn 2001 av franska h├żlsoinstitutet Inserm anger att 10% av de som r├Čker cannabis riskerar att bli beroende, j├żmf├Črt med 30% f├Čr tobak[26].

En holl├żndsk studie fr├źn ├źr 2001 med 7000 deltagare mellan 18-65 ├źr visade att 10% av cannabisr├Čkarna indikerade tecken p├ź beroende under sin livstid[27]

En forskare anser i en litteraturgenomg├źng fr├źn 2007 att cannabis har l├żgre beroenderisk ├żn flera andra droger eftersom endast 7-10% f├źr abstinenssymptom och dessa ├żr milda:

| ŌĆ£ | A degree of physical dependence can occur with cannabis and abrupt discontinuation of use can cause mild withdrawal symptoms (Couper & Logan, 2004). Such dependency occurs in 7 to 10 percent of users (Kalant, 2004), which represents a lower dependency risk than exists for opioids, tobacco, alcohol and benzodiazepines (Grotenhermen, 2003). ŌĆö Review of the literature on cannabis and crash risk (Baldock, 2007)[28] |

ŌĆØ |

Kanadensiska senatens rapport om cannabis fr├źn 2002 drar f├Čljande slutsatser om cannabisberoendet och dess problembild:

| ŌĆ£ | Clinical studies

It is difficult to generalize based on the results of clinical studies, but it is interesting to see to what extent their results are similar to those of epidemiologic studies. Kosten examined the validity of DSM-III R criteria to identify syndromes of dependence on various psychoactive substances including cannabis. He observed that the criteria for syndromes of alcohol, cocaine and opioid dependence were strongly consistent. The results were more ambiguous for cannabis. A criterion-referenced analysis revealed that there were three dimensions to the cannabis dependence syndrome: (1) compulsion ŌĆō indicated by a change in social activities attributable to the drug; (2) difficulty stopping ŌĆō revealed by the inability to reduce use, a return to previous levels after stopping temporarily and a degree of tolerance of the effects; and (3) withdrawal signs ŌĆō revealed by their disappearance with re-use and continuing use despite recognized difficulties. Studies on long-term users In Canada, Hathaway conducted a study between October 2000 and April 2001 to identify problem use and dependence in long-term users based on the DSM-IV criteria. The sample was made of 104 individuals (64 men and 40 women) aged 18 to 55 (mean age 34). 80% had used cannabis on a weekly basis, 51% on a daily basis during the preceding 12 months, and close to half (49%) had used one ounce (28 grams) or more per month. Reasons to use included: to relax (89%), to feel good (81%), to enjoy music or films (72%), because they are bored (64%) or as a source of inspiration (60%). Respondents were asked if they had ever engaged in deviant activity related to cannabis use. The most frequent answer was to have been in an uncomfortable situation in order to get cannabis. Other activities included borrowing money, selling cannabis to support their own drug use, and taking on extra work to buy cannabis. Only 6% ever had recurring legal problems due to their use of cannabis. With respect to dependence, 30% reported a lifetime prevalence of three or more of the criteria, 15% during the 12 months prior to the interview. In light of this finding, the most frequently encountered problems with cannabis have more to do with self-perceptions of excessive use levels than with the drugŌĆÖs perceived impact on health, social obligations and relationships, or other activities. Lending support to the highly subjective nature of his evaluative process, no significant correlations were found between amounts nor frequency of use and the number of reported DSM-IV items. For those whom cannabis dependency problems progress to the point of seeking out or considering formal help, however, the substantive significance of perceived excessive use levels cannot be overlooked. |

ŌĆØ |

I samanfattningen skriver man bl.a att ett fysiskt beroende ├żr praktiskt sett icke-existerande:

| ŌĆ£ | Heavy use of cannabis can result in dependence requiring treatment; however, dependence caused by cannabis is less severe and less frequent than dependence on other psychotropic substances, including alcohol and tobacco.

... In Chapter 7 we determined that physical dependency on cannabis was rare and insignificant. Some symptoms of addiction and tolerance can be identified in habitual users but most of them have no problem in quitting and do not generally require a period of withdrawal. As far as forms of psychological dependency are concerned, the studies are still incomplete but the international data tend to suggest that between 5% and 10% of regular users (using at least in the past month) are at risk of becoming dependent on cannabis. ... What form does cannabis dependency take? Most authors agree that psychological dependency on cannabis is relatively minor. In fact, it cannot be compared in any way with tobacco or alcohol dependency and is even less common than dependency on certain psychotropic medications. We have observed that:

|

ŌĆØ |

Abstinens

Tidiga studier p├ź m├żnniskor gjorda under 1970-talet[31] visade att orala doser med 180-210mg THC (motsvarande 10 jointar) per dag i 10-20 dagar orsakade s├Čmnst├Črningar, rinnande n├żsa, minskad aptit och svettningar som f├Črsvann efter fyra dagar. Samtidigt noterade de att symptomen var relativt milda och var skeptiska kring att dessa symptom uppkom vid normalt rekreationellt bruk. Studier[32][33] har sedermera visat att abstinensen fortfarande var p├ź sitt maximum efter fyra dagar med l├żgre doser och l├żgre antal provdagar.

Sedan dess har man genom djurf├Črs├Čk och studier p├ź m├żnniskor l├żrt sig ├żnnu mera om abstinensen fr├źn cannabis. Men det ├żr f├Črst p├ź senare ├źr som forskarna n├źtt konsensus om att cannabisabstinensen existerar, bevisen f├Čr det ├żr signifikana. Ramstr├Čm n├żmnde lite om det i inledningen. Anledningen till konflikten ├żr att den tidiga forskningen hade m├źnga metodproblem och att resultaten ans├źgs kunna ha alternativa f├Črklaringar, mer om det i n├żsta citat.

DSM-V fr├źn 2013 har inkluderat diagnosen cannabisabstinens, detta efter att flera nya studier st├Čder dess signifikans[34][35][36][37] och Budney som varit drivande vidh├źllit att han ville se en f├Čr├żndring[38].

Det skall dock noteras att det funnits mycket kritik. Den sammanfattas h├żr i en metastudie fr├źn Neil Smith (2001):

| ŌĆ£ | The methods used in measuring abstinence effects have been inconsistent: self-report, observation and a variety of scales are used to assess symptoms. What the majority of these measures do have in common is that they fail to measure adequately the severity of symptoms. Although Wiesbeck and colleagues attempted to model the DSM-IV criteria for substance withdrawal, when constructing a list for cannabis withdrawal symptoms they ignored the other DSM-IV criteria for withdrawal states, which requires ŌĆś. . . clinically signi?cant distress or impairment . . .ŌĆÖ (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Severity of symptoms is not measured in that study (Wiesbeck et al. 1996). When severity is measured many of the symptoms reported are mild and do not reach a clinically signi?cant level. The approach to the issue of severity in these studies is typi?ed by Jones and colleaguesŌĆÖ method of recording symptoms occurring ŌĆśat least onceŌĆÖ (Jones et al. 1976). However, these researchers did add that the withdrawal symptoms that they observed were ŌĆśmild and short-livedŌĆÖ. Where standardized clinical instruments are used to measure severity, results again reveal mild symptom patterns. Kouri and colleagues found a signi?cant increase in depression, as measured by the Hamilton rating scale for depression (Hamilton 1960), between abstinent cannabis smokers and controls (Kouri et al. 1999) However, this score peaked at only six, a subclinical rating on the scale. The variability of symptoms in terms of severity is also clearly observable in Table 1. In the Budney and colleagues study ŌĆśsevereŌĆÖ symptoms were reported by a minority of individuals in every category, and this in a group of individuals meeting current dependence criteria (Budney et al. 1999).

... It is a necessary criterion of most disorders included in DSM-IV that the presence of other mental conditions/alternative explanations are ruled out before a diagnosis is made. All withdrawal studies made some form of psychiatric evaluation prior to selection of their samples. However, Budney et al. (1999) reported that 41% of their sample had a history of psychiatric diagnosis and 79% of Stephens et al. (1993) sample had a diagnosis of a ŌĆśpsychological disorderŌĆÖ according to the SCL-90R (symptoms checklist-90 revised, Derogatis 1983). Crowley and colleagues studied dependence and withdrawal in a population of adolescents with conduct disorders. Although they did ?nd withdrawal symptoms in abstinent users, they recommended that ŌĆś. . . ?ndings from this severely affected clinical population should not be generalised broadly to other adolescentsŌĆÖ (Crowley et al. 1998) (for this reason, the study has been omitted from the list of withdrawal studies described above). Only one study thus far has reported the use of a standardised instrument (current and past psychopathology scales: CAPPS; Endicott & Spitzer 1972) to preselect and omit participants: this study found no withdrawal effects (Greenberg et al. 1976). Other studies reported only that clinical examinations had been conducted by psychiatrists with no further details of past psychiatric history (Babor et al. 1976; Cohen 1976; Jones et al. 1976; Georgotas & Zeidenberg 1979; Haney et al. 1999a, b; Kouri et al. 1999). Although personality differences do not always reach the level of ŌĆśdisorderŌĆÖ, they have been implicated in withdrawal onset and severity in individuals ceasing benzodiazepine use (Tyrer, Owen & Dawling 1983; Rickels et al. 1986; Golombok et al. 1987). The only study to investigate the possible effects of personality on the appearance of withdrawal symptoms following cessation of cannabis use utilized the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI; Hathaway & McKinley 1951) to discover a particular group of traits that appeared to be related to the effects of abstaining from the drug, including anxiety, dependency and ego strength (Bachman & Jones 1979). Factor analysis of the results revealed a trait of ŌĆśego weaknessŌĆÖ in those experiencing withdrawal symptoms. These results concur with studies into benzodiazepines which link withdrawal severity and treatment outcome to ŌĆśdependent personalityŌĆÖ traits (Rickels et al. 1988; Rickels et al. 1999). ... Aside from the withdrawal studies, the main evidence for cannabis causing physical dependence and withdrawal comes from precipitated withdrawal effects using antagonists. These studies may provide evidence for the existence of cannabinoid speci?c receptors and a physiological aspect to the action of THC. However, the long half-life of cannabinoids in the human system under normal conditions make it unlikely that this effect is being recreated in abstinent human users. Cannabis, although having some similarities with opiates and sedatives, should not be grouped together with these drugs which can cause severe impairment and often require medical intervention. There is some evidence for the role of psychological processes being able to alter the effects of cannabis intoxication, and of the role of personality in the withdrawal process. The psychology of dependence and withdrawal should not be neglected in the race to ?nd physiological causes. |

ŌĆØ |

Dr. Budney genomf├Črde en studie 2001[40] som visar starka bevis f├Čr abstinenssymptomen obehag, ├Čnskan att r├Čka cannabis, minskad aptit och s├Čmnsv├źrigheter. Fysiska symptom anses vara svaga eller ej p├źvisbara.

N├źgra ├źr senare, ├źr 2004, presenterade Budney en metastudie om cannabisabstinens. Den redde ut flera fr├źgetecken kring abstinensen som b.la. var framlagda av Smith, och gjorde att fler forskare st├żllde sig p├ź hans sida. H├żr sammanfattar han hur abstinenssymptomen snabbt "peakar" och sedan avtar ├Čver n├źgra veckor:

| ŌĆ£ | Incidence/Prevalence

The incidence of specific abstinence effects gleaned from experimental laboratory studies suggests that the majority of daily marijuana users experience withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt cessation of use. An early inpatient study reported that 55%ŌĆō89% of participants experienced irritability, restlessness, insomnia, or anorexia after discontinuation of oral THC (24ŌĆō26). One outpatient laboratory study reported that more than 50% of heavy cannabis users experienced an increase in symptom severity of at least 30% (3 points on a 10-point scale) on five discrete symptoms (39). Another outpatient study (41) reported that 40% of participants experienced increases of at least 25% (1 point on a 4-point scale) on eight discrete symptoms and that 78% reported such increases for four or more symptoms. The retrospective survey studies also suggest that withdrawal symptoms are experienced by the majority of chronic, heavy cannabis users. Large population studies indicate cannabis withdrawal occurs among a subpopulation of users, with higher prevalence and more symptoms reported by more chronic, frequent, and dependent users (42ŌĆō44). The majority of adults seeking treatment for cannabis abuse or dependence report a history of experiencing cannabis withdrawal (47ŌĆō50), and most report a co-occurrence of four or more symptoms of substantial severity (51). A substantial proportion of adolescents seeking treatment for substance abuse also indicate that they have experienced multiple cannabis withdrawal symptoms (52). In summary, cannabis withdrawal symptoms are reported by a significant proportion of heavy (daily or dependent) marijuana users. The incidence of experiencing multiple symptoms upon cessation of use appears to be more than 50%, and, among treatment seekers, the proportion is likely higher. Time Course The onset of cannabis abstinence symptoms has consistently been observed during the first 1ŌĆō2 days postcessation of cannabis or oral THC administration across several inpatient and outpatient studies (25, 30, 31, 39ŌĆō41). In the only two outpatient studies that examined extended periods of abstinence, peak effects typically occurred between days 2 and 6 (39, 41). Most symptoms appeared to return to baseline or to comparison-group level within 1ŌĆō2 weeks, with moderate variability noted across symptoms and individuals. Most abstinence symptoms followed a transient pattern, peaking shortly after cessation and returning to baseline over time. Sleep problems, particularly unusual dreams, did not return to baseline by the end of a 45-day abstinence period and thus cannot be classified as transient (41). Irritability and physical tension also did not return to baseline during the 28-day abstinence study (39), although irritability did return to baseline in the 45-day study (41). The observation that most transient symptoms returned to baseline and comparison-group levels, combined with the exclusion of persons with psychiatric disorder from these studies, suggests that these abstinence effects are not rebound effects indicative of the participantsŌĆÖ condition before initiation of cannabis smoking. In summary, a well-defined time of onset, peak, and duration has been defined for several symptoms. |

ŌĆØ |

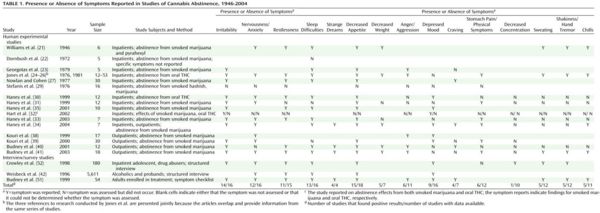

Budney l├żgger ├żven fram ett f├Črslag om vilka abstinenssymptom skall ing├ź i DSM-V. H├żr kan man se att fysisk abstinens fortfarande r├żknas som mindre vanligt:

Common symptoms

- Mood

- Anger or aggression (6/11 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Irritability (14/16 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Nervousness/anxiety (12/16 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Behavioural

- Decreased appetite or weight loss (15/18 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Restlessness (11/15 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Sleep difficulties, including strange dreams (13/16 studier p├źvisar detta)

Less common symptoms/equivocal symptoms

- Physical

- Chills (5/11 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Stomach pain (6/12 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Shakiness (5/12 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Sweating (5/12 studier p├źvisar detta)

- Mood

- Depressed mood (9/16 studier p├źvisar detta)

H├żr ├żr en tabellen med Budneys genomg├źng av studier som p├źvisar abstinenssymptomen som anges ovan. :

Australiska NCPIC (National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre) har sammanst├żllt en guide fr├źn 2009 som handlar om hanterandet av cannabisabstinens. Den sammanfattar Budneys och n├źgra andra forskares resultat:

| ŌĆ£ | The proportion of patients reporting cannabis withdrawal in recent treatment studies has ranged from 50-95% (Budney & Hughes, 2006). Symptoms commonly experienced include sleep difficulty; decreased appetite and weight loss; irritability; nervousness and anxiety; restlessness; and increased anger and aggression. The majority of symptoms peak between day two and six of abstinence and most return to baseline by day 14. Sleep difficulty, anger/aggression, irritability and physical tension have persisted for three to four weeks in some studies (Budney, Moore, Vandrey, & Hughes, 2003; Kouri & Pope, 2000). Strange dreams failed to return to baseline during a 45-day abstinence study (Budney et al., 2003).

Given the inherent bias in treatment seeking samples, for many dependent cannabis users withdrawal may not be a significant hurdle to achieving a period of abstinence. However, even where withdrawal severity is of a similar magnitude to that experienced by people ceasing tobacco use (Vandrey, Budney, Hughes, & Liguori, 2008; Vandrey, Budney, Moore, & Hughes, 2005), withdrawal can of course be a barrier to attaining abstinence. As with other substances, the range and severity of withdrawal symptoms lie on a spectrum and tend to be greater among heavier, dependent users (Budney & Hughes, 2006). It is also probable that cannabis withdrawal discomfort will be greater among people with psychiatric comorbidity (Budney, Novy & Hughes, 1999), amongst whom continued use is also most harmful (Hall, Degenhardt & Lynskey, 2001). |

ŌĆØ |

Man anger ocks├ź att en minskning av dosen ├Čver l├żngre tid f├Črmodligen minskar abstinensbesv├żren hos cannabisr├Čkare som f├Črs├Čker sluta:

| ŌĆ£ | Gradual reduction

The gradual reduction of an agonist substance of dependence is typically associated with less severe and clinically significant withdrawal, because of the less abrupt reversal of neuroadaptive changes that a more gradual taper permits. Such an approach underlies most pharmacologically assisted interventions for substance-related withdrawal (e.g., methadone and buprenorphine taper in opiate withdrawal, and benzodiazepine taper for alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal) (Alexander & Perry, 1991; Lejoyeux, Solomon & Ades, 1998; NSW Department of Health, 2006). Although there is no evidence in the literature about the effect of gradual dose reduction of cannabis on the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the relatively long plasma half-life of various active cannabis metabolites (typically cited as 1-4 days) (Johansson, Halldin, Agurell, Hollister, & Gillespie, 1989; Wall & Perez-Reyes, 1981) suggests that a gradual reduction in cannabis use would be an effective strategy for people with cannabis dependence, where individuals are able to exert some control over their use or where access to their cannabis is regulated by a third party. This is supported by the apparent clinical utility of oral THC in the management of cannabis withdrawal (Budney, Vandrey, Hughes, Moore, & Bahrenburg, 2007; Haney et al., 2004). Advice on gradual cannabis reduction may include smoking smaller bongs or joints, smoking fewer bongs or joints, commencing use later in the day and having goals to cut down by a certain amount by the next review. |

ŌĆØ |

En studie fr├źn 2010[43] visar att abstinensen ├żr h├Čgst den f├Črsta dagen.

En studie fr├źn 2012 visar att kroniska cannabisr├Čkare f├źr h├Čgre grad av abstinenssymptom och man kommer fram till att h├Čgre grad av abstinens leder till fler ├źterfall. Man ├żr inne p├ź samma sp├źr som NCPIC (se citatet ovan), n├żmligen att en minskning av doseringen tiden f├Čre det totala avslutandet, m.a.o. en nedtrappning, kan leda till mindre abstinens och d├żrmed mindre risk f├Čr ├źterfall:

| ŌĆ£ | In conclusion, cannabis withdrawal is clinically significant because it is associated with elevated functional impairment to normal daily activities, and the more severe the withdrawal is, the more severe the functional impairment is. Elevated functional impairment from a cluster of cannabis withdrawal symptoms is associated with relapse in more severely dependent users. Those participants with higher levels of functional impairment from cannabis withdrawal also consumed more cannabis in the month following the end of the experimental abstinence period. Higher levels of cannabis dependence (scores on the SDS) predicted greater functional impairment from cannabis withdrawal. These findings suggest that higher SDS scores can be used to predict problematic withdrawal requiring more intense treatment that can be monitored closely using the Cannabis Withdrawal Scale. Finally and speculatively, the finding that lower levels of cannabis dependence predict lower levels of functional impairment from withdrawal (and thus lower levels of relapse) may indicate that stepped reductions in cannabis use prior to a quit attempt could reduce dependence, and thus reduce levels of withdrawal related functional impairment, improving chances of achieving and maintaining abstinence. Targeting the withdrawal symptoms that contribute most to functional impairment during a quit attempt might be a useful treatment approach (e.g. stress management techniques to relieve physical tension and possible pharmacological interventions for alleviating the physical aspects of withdrawal such as loss of appetite and sleep dysregulation). ŌĆö Quantifying the Clinical Significance of Cannabis Withdrawal (Allsop, 2012)[44] |

ŌĆØ |

L├żs ├żven Science Daily: Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms Might Have Clinical Importance

Metoderna f├Čr att samla in data om studiedeltagarnas symptom har varierat genom ├źren och haft varierande kvalitet. Numera finns ett formul├żr som kallas "The Cannabis Withdrawal Scale" och anv├żnds f├Čr att kontrollera abstinenssymptom i studier[45] och f├Črmodligen har med alla n├Čdv├żndiga delar, samt st├żller fr├źgorna p├ź r├żtt s├żtt. Enligt formul├żrets skapare visar egna studier att man f├źr mest respons p├ź intensiva dr├Čmmar, s├Čmnsv├źrigheter och aggressivitet[46]. Den kommer f├Črmodligen anv├żndas i framtida studier.

Metoder f├Čr att minska abstinensen

Man har l├żnge haft uppfattningen att det inte finns n├źgra metoder f├Čr att lindra eller d├żmpa cannabisabstinens, men p├ź senare tid har man n├źtt n├źgra intressanta genombrott[47].

En studie fr├źn 2012 visar att nikotinavv├żnjningsmedlet Bupropion[48] (i form av l├żkemedlet Zyban) ├żr effektivare ├żn placebo n├żr det g├żller att lindra ├Čnskan att r├Čka cannabis och ledde till f├żrre ├źterfall under studiens g├źng[49].

Kliniska studier med gabapentin[50] och N-acetylcystein[51] verkar ocks├ź lovande f├Čr att minska abstinensen.

Det finns t.o.m indikationer som tyder p├ź att man kan anv├żnda cannabis f├Čr att bli av med sitt cannabisberoende! Brasilianska l├żkare rapporterar i en fallbeskrivning fr├źn 2013[52] att en patient som fick 300-600mg CBD per dag i 11 dagar upplevde att abstinensen f├Črsvann. Forskare vid University College i London genomf├Čr i skrivande stund (2015) tv├ź kliniska studier d├żr man dels skall ta reda p├ź vilken dos som ├żr effektivast, varefter resultaten fr├źn 60 cannabisanv├żndare som f├źr CBD skall j├żmf├Čras med 60 som f├źr placebo[53].

En studie fr├źn 2011[54] visar att Aerobics (kan f├Črmodligen ers├żttas med annan motion) ├żr effektivt f├Čr att reducera cannabisberoende, ├żven hos personer som inte vill sluta. Efter bara ett f├źtal tr├żningspass hade m├żngden cannabis de anv├żnde halverats. Det verkar med andra ord inte vara speciellt sv├źrt att tygla abstinensen fr├źn ett beroende:

| ŌĆ£ | During the study their craving for and use of cannabis was cut by more than 50 percent after exercising on a treadmill for 10 30-minute sessions over a two-week period.

"This is 10 sessions but it actually went down after the first five. The maximum reduction was already there within the first week," said co-author Peter Martin, M.D., director of the Vanderbilt Addiction Center. "There is no way currently to treat cannabis dependence with medication, so this is big considering the magnitude of the cannabis problem in the U.S. And this is the first time it has ever been demonstrated that exercise can reduce cannabis use in people who don't want to stop." |

ŌĆØ |

J├żmf├Črelse med andra droger

En j├żmf├Črelse av olika drogers grad av beroende-, tolerans-och abstinensframkallande egenskaper j├żmf├Črdes av Dr. Jack E. Henningfield, chef f├Čr klinisk farmakologi vid beroendeforskningscentret vid myndigheten NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) i en artikel i New York Times 1994[56] visade att cannabis gav mindre beroende, abstinens och tolerans ├żn koffein.

I Professor Bernard Roques bed├Čmning fr├źn 1998 av olika drogers farlighet som finns med i den kanadensiska rapporten om cannabis[57] visar att cannabis ger en l├źg grad av fysiskt och psykiskt beroende:

| Drog | Grad av fysiskt beroende | Grad av psykiskt beroende |

|---|---|---|

| Heroin | V├żldigt h├Čg | V├żldigt h├Čg |

| Kokain | L├źg | H├Čg men intermittent |

| MDMA | V├żldigt l├źg | ? |

| Psykostimulanter | L├źg | Medelh├Čg |

| Alkohol | V├żldigt h├Čg | V├żldigt h├Čg |

| Benzodiazepiner | Medelh├Čg | H├Čg |

| Cannabinoider | L├źg | L├źg |

| Tobak | H├Čg | V├żldigt h├Čg |

Institute Of Medicines metastudie fr├źn 1999 anger att cannabisabstinensen ├żr mild j├żmf├Črt med droger som har fysiska symptom:

| ŌĆ£ | Withdrawal

A distinctive marijuana and THC withdrawal syndrome has been identified, but it is mild and subtle compared with the profound physical syndrome of alcohol or heroin withdrawal. The symptoms of marijuana withdrawal include restlessness, irritability, mild agitation, insomnia, sleep EEG disturbance, nausea, and cramping. In addition to those symptoms, two recent studies noted several more. A group of adolescents under treatment for conduct disorders also reported fatigue and illusions or hallucinations after marijuana abstinence (this study is discussed further in the section on "Prevalence and Predictors of Dependence on Marijuana and Other Drugs"). In a residential study of daily marijuana users, withdrawal symptoms included sweating and runny nose, in addition to those listed above. A marijuana withdrawal syndrome, however, has been reported only in a group of adolescents in treatment for substance abuse problems and in a research setting where subjects were given marijuana or THC daily. Withdrawal symptoms have been observed in carefully controlled laboratory studies of people after use of both oral THC and smoked marijuana. In one study, subjects were given very high doses of oral THC: 180-210 mg per day for 10-20 days, roughly equivalent to smoking 9-10 2% THC cigarettes per day. During the abstinence period at the end of the study, the study subjects were irritable and showed insomnia, runny nose, sweating, and decreased appetite. The withdrawal symptoms, however, were short lived. In four days they had abated. The time course contrasts with that in another study in which lower doses of oral THC were used (80-120 mg/day for four days) and withdrawal symptoms were still near maximal after four days. In animals, simply discontinuing chronic heavy dosing of THC does not reveal withdrawal symptoms, but the "removal" of THC from the brain can be made abrupt by another drug that blocks THC at its receptor if administered when the chronic THC is withdrawn. The withdrawal syndrome is pronounced, and the behavior of the animals becomes hyperactive and disorganized. The half-life of THC in brain is about an hour. Although traces of THC can remain in the brain for much longer periods, the amounts are not physiologically significant. Thus, the lack of a withdrawal syndrome when THC is abruptly withdrawn without administration of a receptor-blocking drug is probably not due to a prolonged decline in brain concentrations. |

ŌĆØ |

Man drar ├żven f├Čljande sammanfattande slutsatser:

| ŌĆ£ |

ŌĆö Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base (Institute Of Medicine, 1999)[58] |

ŌĆØ |

Man inkluderar ├żven en tabell d├żr abstinenssymptom fr├źn olika droger j├żmf├Črs[59]). Notera att cannabis saknar de flesta fysiska abstinenssymptom som de andra drogerna har:

| Nicotine | Alcohol | Marijuana | Cocaine | Opioids |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restlessness, Irritability, Dysphoria, Impatience & hostility, Dysphoria, Depression, Anxiety, Difficulty concentrating, Decreased heart rate, Increased appetite or weight gain | Irritability, Sleep disturbance, Nausea, Tachycardia (Hypertension), Sweating, Seizures, Alcohol craving, Delirium tremens (severe agitation, confusion, visual hallucinations, fever, profuse sweating, nausea, diarrhea, dilated pupils), Tremor | Restlessness, Irritability, Mild agitation, Insomnia, Sleep EEG disturbance, Nausea, Cramping | Dysphoria, Depression, Sleepiness & fatigue, Bradycardia, Cocaine craving | Restlessness, Irritability, Dysphoria, Anxiety, Insomnia, Nausea, Cramping, Muscle aches, Increased sensitivity to pain, Opioid craving |

├även i kanadensiska senatens rapport fr├źn 2002[30] anser man att tobak och alkohol ger ett starkare beroende.

Ett par uppskattningar av beroendet av olika droger har gjorts av David Nutt 2007[60] och av Jan van Amsterdam 2010[61]:

| Drog | Medelv├żrde (Amsterdam et al) | Medelv├żrde (Nutt) | Njutning (Nutt) | Psykiskt beroende (Nutt) | Fysiskt beroende (Nutt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin | 2.89 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Crack | 2.82 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tobak | 2.82 | 2.21 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Metadon | 2.68 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kokain | 2.13 | 2.39 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Metamfetamin | 2.24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Alkohol | 2.13 | 1.93 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Amfetamin | 1.95 | 1.67 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Benzodiazepiner | 1.89 | 1.83 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| GHB | 1.71 | 1.19 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Cannabis | 1.13 | 1.51 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Ketamin | 0.84 | 1.54 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| Khat | 0.76 | 1.04 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| Ecstasy | 0.61 | 1.13 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| LSD | 0.03 | 1.23 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Psilocybin | 0.03 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Under 2008 har det gjorts studier som j├żmf├Čr abstinensen fr├źn cannabis och tobak. Resultaten ├żr ├Čverraskande sett till tidigare uppskattningar eftersom man kommer fram till att cannabis och tobak ger likv├żrdig abstinens sett till intensitet och typer av symptom. N├źgot som inte ├żr lika ├Čverraskande ├żr att man ser att kombinationen av drogerna ger starkare abstinens ├żn enbart cannabis eller tobak[62][63].

En metastudie fr├źn 2012 visar ett samband mellan kombinationen av tobak och cannabis och ├Čkade sv├źrigheter att sluta med cannabis. R├Čkare av enbart cannabis hade l├żttare att sluta[64]. Detta ├żr intressant d├ź m├źnga tidigare studier om cannabisberoende inte lade s├ź stor vikt vid att m├źnga cannabisr├Čkare blandar cannabis och tobak[65] vilket kan st├Čra forskningsresultaten, och skapa felk├żllor.

S├Čtsaker ├żr mer beroendeframkallande ├żn kokain!

Att socker ├żr extremt beroendeframkallande ├żr ett p├źst├źende man h├Čr ibland, ofta heter det att det ├żr mer beroendeframkallande ├żn heroin eller kokain. M├źnga skrattar och avf├żrdar det som nonsens, men faktum ├żr att beroendet av s├Čtsaker ├żr bland det starkaste vi k├żnner till.

I en studie fr├źn 2007[66] visade forskare att r├źttor f├Čredrog sackarin framf├Čr kokain, ├żven om r├źttorna blev kokainberoende innan sackarinl├Čsningen introducerades. Sackarin ├żr ett s├Čtningsmedel som ├źterfinns i bl.a suketter, bords├Čtningsmedel och andra light-produkter. Det tas inte upp av kroppen och m├Čssen kan d├żrmed inte f├Črdragit s├Čtningsmedlet ut energisynpunkt (vilket de ├żven g├Čr i studier med socker) utan det handlar om ett beroende som utvecklas genom stimulering av tungans s├Čtmareceptorer. Detta utl├Čser bel├Čningseffekter i hj├żrnan, som i sin tur ├żr kraftigare ├żn bel├Čningen av att ta kokain:

| ŌĆ£ | Virtually all rats preferred saccharin over intravenous cocaine, a highly addictive drug. The preference for saccharin is not attributable to its unnatural ability to induce sweetness without subsequent caloric input because the same preference was also observed with an equipotent concentration of sucrose, a natural sugar. Importantly, the preference for saccharin sweet taste was not surmountable by increasing doses of cocaine and was observed despite either cocaine intoxication, sensitization or intake escalation ŌĆō the latter being a hallmark of drug addiction. In addition, in several cases, the preference for saccharin emerged in rats which had originally developed a strong preference for the cocaine-rewarded lever. Such reversals of preference clearly show that in our setting, animals are not stuck with their initial preferences and can change them according to new reward contingencies. Finally, the preference for saccharin was maintained in the face of increasing reward price or cost, suggesting that rats did not only prefer saccharin over cocaine (ŌĆślikingŌĆÖ) but they were also more willing to work for it than for cocaine (ŌĆśwantingŌĆÖ). As a whole, these findings extend previous research by showing that an intense sensation of sweetness surpasses maximal cocaine stimulation, even in drug-sensitized and -addicted users. The absolute preference for taste sweetness may lead to a re-ordering in the hierarchy of potentially addictive stimuli, with sweetened diets (i.e., containing natural sugars or artificial sweeteners) taking precedence over cocaine and possibly other drugs of abuse. ŌĆö Lenoir(2007)[66] |

ŌĆØ |

Man har i en annan studie sett att h├Čg sockerkonsumtion orsakar samma typ av receptorf├Čr├żndringar som nikotinberoende:

| ŌĆ£ | In the current study, we also found that long-term sucrose exposure resulted in an increase in ╬▒4╬▓2* and a decrease in ╬▒6╬▓2* nAChR receptors in the NAc. Interestingly, administration of nicotine results in similar changes in the ╬▒4╬▓2* and ╬▒6╬▓2* nAChRs levels, and to a similar magnitude as that obtained in the present study with sucrose. Although the mechanisms responsible for this are still not fully understood, it has been suggested that changes in ╬▒4╬▓2* and ╬▒6╬▓2* nAChRs contribute to nicotine re-enforcement and self-administration. By analogy, the observed changes in nAChRs with sucrose intake may underlie the addictive properties of sucrose. ŌĆö Shariff (2016)[67] |

ŌĆØ |

Är orsaken till beroendet drogen eller brukaren?

Vi har alla f├źtt h├Čra att drogens effekt ├żr det som skapar beroendet, att hj├żrnan blir kemiskt beroende av kickarna. Till en viss grad st├żmmer det, men det ├żr en kraftig f├Črenkling som d├Čljer en viktig faktor som ├żr kan avg├Čra beroendepotentialen. Psykologin inverkar mer ├żn man tror.

Under slutet av 1970-talet genomf├Črde professor Bruce Alexander vid Simon Fraser University en studie kallad "Rat Park"[68][69] som studerade tillf├Črlitligheten av tidigare studier d├żr man gjort r├źttor narkotikaberoende. I experimentet s├ź anv├żndes flera grupper med r├źttor. Tv├ź grupper fick v├żxa upp i sm├ź burar d├żr de blev beroende av droger, vilket inte var n├źgon st├Črre sv├źrighet, de kunde v├żlja mellan att dricka vatten eller morfinl├Čsning och valde omedelbart det sistn├żmnda. Sedan l├żt man en av grupperna med beroende r├źttor flytta ut i "r├źttparken", en 200 g├źnger st├Črre bur d├żr det fanns "ickeberoende" r├źttor fr├źn en tredje grupp att socialisera med, samt massor med leksaker, hjul att springa i och andra saker som gjorde r├źttlivet intressant och njutbart. R├źttorna kunde forts├żtta v├żlja att dricka vatten eller morfinl├Čsningen och nu gick de "beroende" r├źttorna ├Čver till att dricka vatten. Inte ens n├żr man gjorde morfinl├Čsningen s├Čtare s├ź ville r├źttorna ha den:

| ŌĆ£ | In the early 1960s, researchers at the University of Michigan perfected devices which allowed relatively free-moving rats to inject themselves with drugs. After implantation of a needle in one of their veins connected to a pump via a tube running through the ceiling of a special Skinner box, rats could inject themselves with a drug simply by pressing a lever. By the end of the 1970s, hundreds of experiments with apparatus of this sort had shown that rats, mice, monkeys, and other captive mammals will self-inject large doses of heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, and a number of other drugs (Woods, 1978).

Many people concluded that these data also constituted proof for the belief in drug-induced addiction. If most or all animals in an experimental group inject heroin and cocaine avidly and to the detriment of their health (as they did in some experiments), does it not follow that the power of these drugs to instill a need for future consumption transcends species and culture and is simply a basic fact of mammalian existence? One eminent American scientist put it this way: "If a monkey is provided with a lever, which he can press to self-inject heroin, he establishes a regular pattern of heroin use--a true addiction--that takes priority over the normal activities of his life...Since this behaviour is seen in several other animal species (primarily rats), I have to infer that if heroin were easily available to everyone, and if there were no social pressure of any kind to discourage heroin use, a very large number of people would become heroin addicts." (Goldstein, 1979, 342). But this statement is in direct contradiction to careful observations of the era in which heroin was freely available in North America and observations of people given relatively free access to opiate drugs in PCA machines, described above. Moreover, some researchers have pointed out that opiate ingestion by laboratory animals could be understood as a way that the animals cope with the stress of social and sensory isolation and the restriction of movement that is imposed by the complex self-administration apparatus. Other researchers pointed out that the mere regular use of a drug by animals or human beings is not equivalent to addiction, as discussed above. To determine whether the self-injection of heroin in these experiments could be an artifact of social isolation, a group of researchers at Simon Fraser University began a series of experiments in the late 1970s which were eventually dubbed the "Rat Park" experiments. Albino rats served as subjects and morphine hydrochloride, which is equivalent to heroin, as the experimental drug. Laboratory rats are gregarious, curious, active creatures. Their ancestors, wild Norway rats, are intensely social and hundreds of generations of laboratory breeding have left many social instincts intact. Therefore, it is conceivable that the self-medication hypothesis might provide the most parsimonious explanation for the self-administration of powerful drugs by rats that were raised in isolated metal cages and subjected to surgical implantations in the hands of a eager (but seldom skillful) graduate student followed by being tethered in a self-injection apparatus. The results of self-injection experiments would not show that claim B was true so much as that severely distressed animals, like severely distressed people, will relieve their distress pharmacologically if they can (Weissman and Haddox, 1989). My colleagues at Simon Fraser University and I built the most natural environment for rats that we could contrive in the laboratory. "Rat Park", as it came to be called, was airy and spacious, with about 200 times the square footage of a standard laboratory cage. It was also scenic, (with a peaceful British Columbia forest painted on the plywood walls), comfortable (with empty tins, wood scraps, and other desiderata strewn about on the floor), and sociable (with 16-20 rats of both sexes in residence at once). In the rat cages, the ratsŌĆÖ appetite for morphine was measured by fastening two drinking bottles, one containing a morphine solution and one containing water, on each cage and weighing them daily. In Rat Park, measurement of individual drug consumption was more difficult, since we did not want to disrupt life in the presumably idyllic rodent community. We built a short tunnel opening into Rat Park that was just large enough to accommodate one rat at a time. At the far end of the tunnel, the rats could release a fluid from either of two drop dispensers. One dispenser contained a morphine solution and the other an inert solution. The dispenser recorded how much each rat drank of each fluid. A number of experiments were performed in this way (for a more detailed summary, see Alexander et al., 1985), all of which indicated that rats living in Rat Park had little appetite for morphine. In some experiments, we forced the rats to consume morphine for weeks before allowing them to choose, so that there could be no doubt that they had developed strong withdrawal symptoms. In other experiments, I made the morphine solution so sickeningly sweet that no rat could resist trying it, but we always found less appetite for morphine in the animals housed in Rat Park. Under some conditions the animals in the cages consumed nearly 20 times as much morphine as the rats in Rat Park. Nothing that we tried instilled a strong appetite for morphine or produced anything that looked like addiction in rats that were housed in a reasonably normal environment. ... I believe these results, which have subsequently been extended by other experimenters (e.g., Bozarth, Murray, and Wise, 1989; Schenk, et al., 1987; Shaham, et al., 1992) show that the earlier animal self-administration studies provide no real empirical support for the belief in drug-induced addiction. The intense appetite of isolated experimental animals for heroin and cocaine in self-injection experiments tells us nothing about the responsiveness of normal animals and people to these drugs. Normal people can ignore heroin and addiction even when it is plentiful in their environment, and they can use these drugs with little likelihood of addiction, as discussed above. Rats from "Rat Park" seem to be no less discriminating. |

ŌĆØ |

Alexander menar att ett par p├źst├źenden som ofta ├źterupprepas av samh├żllet inte ├żr empiriskt h├źllbara:

- P├źst├źende A: Alla, eller de flesta som anv├żnder mer heroin eller kokain ut├Čver en viss minimim├żngd blir beroende.

- P├źst├źende B: Oavsett hur stor andelen anv├żndarna av heroin och kokain som blir beroende, s├ź ├żr beroendet orsakat av drogen.

| ŌĆ£ | Thus, Claim A is demonstrably false and Claim B is no more than one of a number of unsubstantiated, but plausible explanations for the fact that some drug users become addicts. The belief in drug-induced addiction, at least with respect to heroin and cocaine, has no status as empirical science, although it has not been disproven. It is believed for some reason other than its empirical support ŌĆö The Myth of Drug-Induced Addiction (Bruce K. Alexander)[69] |

ŌĆØ |

Han f├Čr fram en alternativ hypotes som inneb├żr att r├źttor v├żljer att ta droger i de sm├ź burarna f├Čr att de lider av depression eller rastl├Čshet. Det ├żr ungef├żr samma f├Črh├źllanden som ligger bakom majoriteten av m├żnskliga missbrukares beroendeproblem. Anledningen till att de tog drogerna s├ź ofta var att de blev beroende av att f├Črsvinna fr├źn vardagens bekymmersamma tillvaro.

L├żs ├żven hans artikel The Rise and Fall of the Official View of Addiction (2014).

Senare studier av andra forskare har ocks├ź visat att en berikad milj├Č minskar morfinberoendet hos m├Čss[70].

En metaanalys fr├źn 2016 granskade 26 studier om cannabisberoende f├Čr att utr├Čna om man kan dra n├źgra samband mellan anledningarna till att personer b├Črjar anv├żnda cannabis och att de blir beroende. Man kom till slutsatsen att en stor riskfaktor f├Čr cannabismissbruk ├żr redan existerande psykiska sjukdomar eller bakomliggande trauman. Personer som ├żr beroende har i st├Črre utr├żckning anv├żnt cannabis f├Čr att d├żmpa k├żnslor av stress, ├źngest, l├źg sj├żlvk├żnsla etc:

| ŌĆ£ | Numerous factors were shown to have an impact on transition to cannabis dependence. In particular, a wide range of mental disorders has been linked to an elevated risk of developing cannabis dependence. One can infer from some studies that cannabis use alone will lead directly to dependence. Nevertheless, low rates of dependence disorder among users seem to contradict this hypothesis. Nocon et al. found that (frequent) use alone does not have to be necessarily linked with cannabis dependence; even regular cannabis use of 2 days per week was associated with a relatively low risk of becoming dependent. It appears that adverse circumstances like traumatic experiences or comorbid mental disorders play a crucial role in this process - even though it cannot be proven beyond a doubt.

...motives for dependent use appeared to differ from those for occasional use. This is in line with evidence from some studies; the notion was put forward that persons dependent on cannabis might differ from infrequent and non-dependent users in having other motives like wishing to reduce negative affect and tension, to cope with stressors or to manage symptoms. |

ŌĆØ |

K├żllor

- Ōåæ Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game (Koepp, 1998)

- Ōåæ The neural basis of video gaming (K├╝hn, 2011)

- Ōåæ Management of moderate and severe alcohol withdrawal syndromes (Hoffman, 2012)

- Ōåæ Wikipedia: Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- Ōåæ 5,0 5,1 5,2 Folkh├żlsoinstitutet - Skador av hasch och marijuana

- Ōåæ 8 myter om Cannabis

- Ōåæ Mobilisering mot narkotika 2003 - ├är cannabis ofarligt?

- Ōåæ Cannabis och farlighet sid.6 (Thomas Lundqvist, 2003)

- Ōåæ 9,0 9,1 Cannabis, beroende och behandling (Thomas Lundqvist, 2011)

- Ōåæ Alla vill slippa ifr├źn missbruket (Narkotikafr├źgan nr 1, 2001)

- Ōåæ Haschboken (Barbro Holmberg, Folkh├żlsoinstitutet, 1994)

- Ōåæ American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. (pp. 181-183)

- Ōåæ American Psychiatric Association 2013: Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Ōåæ DSM-5 Proposed Revisions Include New Category of Addiction and Related Disorders New Category of Behavioral Addictions Also Proposed

- Ōåæ 15,0 15,1 Medscape: Cannabis-Related Disorders Clinical Presentation

- Ōåæ Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder, 2012-2013: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsŌĆōIII (Hasin, 2015)

- Ōåæ WHO: Dependence syndrome

- Ōåæ IDC-10: Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10-F19)

- Ōåæ Dopamine and the Dependence Liability of Marijuana (Gettman, 1997)

- Ōåæ 20,0 20,1 Cannabis reinforcement and dependence role of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor (Cooper, 2008)

- Ōåæ Marijuana and cannabinoid regulation of brain reward circuits (Lupica, 2004)

- Ōåæ Cannabis cue-elicited craving and the reward neurocircuitry (Filbey, 2011)

- Ōåæ A Brain on Cannabinoids: The Role of Dopamine Release in Reward Seeking (Oleson, 2012)

- Ōåæ Johnston, L.D. et al, Drug Use Among American High School Seniors, College Students and Young Adults, 1975-1990,Vol II, Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1991), p 31.

- Ōåæ Hall W, Room R, Bondy S. Comparing the health and psychological risks of alcohol, cannabis, nicotine and opiate use. In: Kalant H, Corrigan W, Hall W, Smart R, eds. The health effects of cannabis. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation, 1999, pp. 477-508.

- Ōåæ Inserm. Cannabis - quels effects sur le comportement et la sant├® ? (Inserm, Institut National de la Sant├® et de la Recherche M├®dicale, 2001)

- Ōåæ Van Laar, M., et al., (2001) National Drug Monitor. Jaarbericht 2001. Utrecht: NDM Bureau.

- Ōåæ Review of the literature on cannabis and crash risk (Baldock, 2007)

- Ōåæ Cannabis : Our Position For A Canadian Public Policy. Report Of The Senate Special Committee On Illegal Drugs (2002)

- Ōåæ 30,0 30,1 Cannabis : Our Position For A Canadian Public Policy. Report Of The Senate Special Committee On Illegal Drugs. Summary (2002)

- Ōåæ Jones RT, Benowitz N, Bachman J. Clinical studies of tolerance and dependence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 282:221-239 (1976).

- Ōåæ Haney M, Ward AS, Comer SD, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. 1999. Abstinence symptoms following smoked marijuana in humans. Psychopharmacology 141:395ŌĆö404.

- Ōåæ Haney M, Comer SD, Ward AS, Foltin RW, Fischman MW: Abstinence symptoms following oral THC administration to humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 14:385ŌĆō394

- Ōåæ Diagnostic criteria for cannabis withdrawal syndrome (Gorelick, 2012)

- Ōåæ Cannabis withdrawal is common among treatment-seeking adolescents with cannabis dependence and major depression, and is associated with rapid relapse to dependence (Cornelius, 2008)

- Ōåæ Cannabis Withdrawal Among Non-Treatment-Seeking Adult Cannabis Users (Copersino, 2010)

- Ōåæ Cannabis withdrawal symptoms in non-treatment-seeking adult cannabis smokers (Levin, 2010)

- Ōåæ Psychiatric Times 2011-04-28: Marijuana Withdrawal Syndrome: Should Cannabis Withdrawal Disorder Be Included in DSM-5? By Alan J. Budney, PhD

- Ōåæ A review of the published literature into cannabis withdrawal symptoms in human users (Smith, 2001)

- Ōåæ Marijuana Abstinence Effects in Marijuana Smokers Maintained in Their Home Environment (Budney, 2001)

- Ōåæ Review of the Validity and Significance of Cannabis Withdrawal Syndrome (Budney, 2004)

- Ōåæ 42,0 42,1 Management of cannabis withdrawal (Adam Winstock & Toby Lea, NCPIC, 2009)

- Ōåæ Cannabis withdrawal severity and short-term course among cannabis-dependent adolescent and young adult inpatients (Preuss, 2010)

- Ōåæ Quantifying the Clinical Significance of Cannabis Withdrawal (Allsop, 2012)

- Ōåæ NCPIC: Cannabis Withdrawal Scale

- Ōåæ The Cannabis Withdrawal Scale development: patterns and predictors of cannabis withdrawal and distress (Allsop, 2011)

- Ōåæ Novel Pharmacologic Approaches to Treating Cannabis Use Disorder (Balter, 2014)

- Ōåæ Wikipedia: Bupropion

- Ōåæ Bupropion Reduces Some of the Symptoms of Marihuana Withdrawal in Chronic Marihuana Users: A Pilot Study (Penetar, 2012)

- Ōåæ A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults (Mason, 2012) pdf-version

- Ōåæ A double-blind randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in cannabis-dependent adolescents (Gray, 2012)

- Ōåæ Cannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis withdrawal syndrome: a case report (Crippa, 2013)

- Ōåæ Gateway to Research: Cannabidiol: a novel treatment for cannabis dependence?

- Ōåæ Aerobic Exercise Training Reduces Cannabis Craving and Use in Non-Treatment Seeking Cannabis-Dependent Adults (Buchowski, 2011)

- Ōåæ Science Daily 2011-03-08: Exercise Can Curb Marijuana Use and Cravings, Study Finds

- Ōåæ Dr. Jack E. Henningfield of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, New York Times, Aug. 2, 1994: Is Nicotine Addictive? It Depends on Whose Criteria You Use.

- Ōåæ Danger Factors of ŌĆ£drugsŌĆØ (reprinted from Roques, B. (1999), page: 296. Excerpts from the Roques report, ordered by B. Kouchner, released in June 1998, tidningsartiklar fr├źn Frankrike 1998 samt Roques tabell ├źterpublicerad av Kanadensiska Senaten: Comparative Harms of Cannabis: Overview Table, Roques Report ŌĆÖ98 (p. 182)

- Ōåæ 58,0 58,1 Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base (Institute Of Medicine, 1999)

- Ōåæ O'Brien CP. 1996. Drug addiction and drug abuse. In: Harmon JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Gilman A G. Editor Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 9th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 557-577

- Ōåæ Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. (Nutt, 2007) finns ├żven som pdf-version

- Ōåæ Ranking the Harm of Alcohol, Tobacco and Illicit Drugs for the Individual and the Population (van Amsterdam, 2010) finns ├żven som pdf-version

- Ōåæ A within-subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances (Vandrey & Budney 2008)

- Ōåæ Comparison of cannabis and tobacco withdrawal: Severity and contribution to relapse (Budney & Vandrey, 2008)

- Ōåæ Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. (Peters, 2012)

- Ōåæ Adding Tobacco to CannabisŌĆöIts Frequency and Likely Implications (Belanger, 2011)

- Ōåæ 66,0 66,1 Intense Sweetness Surpasses Cocaine Reward (Lenoir, 2007)

- Ōåæ Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Modulators Reduce Sugar Intake (Shariff, 2016)

- Ōåæ Wikipedia: Rat Park

- Ōåæ 69,0 69,1 69,2 The Myth of Drug-Induced Addiction (Bruce K. Alexander)

- Ōåæ Effects of enriched environment on morphine-induced reward in mice (Xu, 2007)

- Ōåæ Psychosocial Determinants of Cannabis Dependence: A Systematic Review of the Literature (Schlossarek, 2016)

Detta ├żr bara en liten del av Legaliseringsguiden. Klicka p├ź l├żnken eller anv├żnd rullistan nedan f├Čr att l├żsa mer om narkotikapolitiken, argumenten f├Čr en avkriminalisering & legalisering, genomg├źngar av cannabis p├źst├źdda skadeverkningar, medicinska anv├żndningsomr├źden och mycket mera. Det g├źr ├żven att ladda ner hela guiden som pdf.

Sidan ├żndrades senast 2 januari 2020 klockan 06.01.

Den h├żr sidan har visats 32┬Ā655 g├źnger.